BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1076-en.html

, Dana Mohammad-Aminzadeh2

, Dana Mohammad-Aminzadeh2

, Erfan Soleimani sefat1

, Erfan Soleimani sefat1

, Nasrin Sudmand1

, Nasrin Sudmand1

, Jalal Younesi

, Jalal Younesi

3

3

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Psychology & Education, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. , jyounesi@uswr.ac.ir

1. Objectives

With aging, individuals gradually lose some of their physiological and psychosocial functions, and deprivation of social activities makes the elderly prone to depression and increases their sense of loneliness [1]. Loneliness makes the elderly susceptible to depression [2]. Feeling lonely and depressed are unpleasant and annoying states, which are tied together. Deterministic thinking has an important role in mental health, especially in increasing depression and anxiety as a destructive factor in disturbing the balance between hope and fear [3]. This distortion is shaped by cognitive inflexibility in the mind and is, thus, one of the major causes of depression and other psychological incompatibilities [4, 5]. Accordingly, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between deterministic thinking and depression and loneliness in the elderly.

The present study was descriptive-correlational, and its population included all aged women and men over the age of 60 who were residents of Kahrizak Nursing center of Karaj in 2014-2015. A total of 142 elderly people (79 women and 63 men) were selected through the available sampling method and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included those elderly who were members of the population protected and had files during the research period. Exclusion criteria included the transfer of individuals from one geographical area to another and death. The questionnaire was distributed among the participants, who were also interviewed by the researchers. From the ethical considerations of this research, it can be said that for all subjects, nature, the purpose and the confidentiality of the results were explained to the participants. In addition, they were explained that their name and identity will remain confidential and that the results obtained will be available to individuals and institutions. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. To investigate the depression status of the elderly, the short form of the Geriatric Depression scale (GDS) questionnaire was used to assess loneliness; the original version of the questionnaire had 30 questions, but we considered only 20 questions in our analysis. The GDS scale was developed in the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) by Russell et al. in 1978 [6]. For measuring definitive thinking, the deterministic thinking scale of Younesi and Mirafzal was used. This questionnaire has 36 questions, whose responses were rated using the Likert Scale (score 1 for “I totally agree” up to score 4 for “I totally disagree”) [7].

3. Results

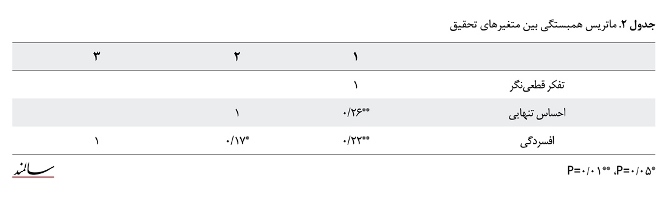

The data from the questionnaire were entered into the AMOS software for analysis using path analysis. Path analysis is considered as a type of structural equation model that includes only the model of causal structure. In fact, path analysis can be done only on the observed variables. First, to examine the status of the variables studied in the target population, the mean of variables was evaluated. The mean of definitive thinking, loneliness, and depression was 118.50, 70.80 and 12.55, respectively. According to the results of Table 1, loneliness and depression had a positive and significant relationship with deterministic thinking in the elderly at level 0.01. In the present study, depression and loneliness also have a positive and significant relationship in elderly people at level 0.05.

Based on the results obtained from the path model test under the AMOS software, the most important indicators of the fitting of the research model included Chi-Square (0.332), degree of freedom (1), normalized Chi-square (0.332), good fit index (0.899), adaptive fit index (0.999), and root mean square error estimate (0.001). Therefore, the developed model is suitable, and there is no need to modify the model. The results indicated that the relationship between deterministic thinking and a sense of loneliness was significant with a significant level of less than 0.001 and the non-standard regression coefficient of 0.054. Deterministic thinking was found to have a positive and significant relationship with loneliness. Also considering that relationship between deterministic thinking and depression is significant at the level less than 0.001 and the non-standard regression coefficient equal to 0.034, deterministic thinking has a positive and significant relationship with depression. According to the results, deterministic thinking with standard coefficients equal to 0.264 and 0.280 have a positive and significant relationship with loneliness and depression in the elderly people living in Karaj Nursing center. On the other hand, the results of path analysis showed that the in

4. Conclusion

According to the results, loneliness has a positive and significant relationship with deterministic thinking among elderly people. In other words, the more the elderly are likely to predict events and incidence definitively, the more they are likely to feel alone. Other findings of the study showed that depression has a positive and significant relationship with deterministic thinking among the elderly. This is because the elderly people often find events and incidence to be certain, and thus, the possibility of having a negative attitude towards themselves, world, and future will be higher. Given these results, we can say that older people whose scores are higher in definitive thinking feel lonelier and are more likely to develop depression. Therefore, performing psychological interventions to challenge the cognitive distortion of deterministic thinking and paying attention to mental health of the elderly are of great importance.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

در نیمه دوم قرن بیستم و ابتدای قرن بیستویکم به دلیل افزایش امید به زندگی و کاهش تدریجی میزان موالید، جمعیت سالمندان در تمامی کشورها از جمله ایران روبهافزایش بوده است [1]. حدود 10 درصد جمعیت جهان را سالمندان (افراد بیشتر از 65 سال) تشکیل میدهند که بیش از 60 درصد این افراد در کشورهای درحالتوسعه زندگی میکنند [3 ،2]. در ایران نیز طبق آخرین سرشماری عمومی در سال 1385، حدود 25/7 درصد از جمعیت، یعنی بیش از 5 میلیون نفر را سالمندان بیش از 60 سال تشکیل میدهند و پیشبینیهای جمعیتی حاکی از آن است که طی 25 سال آینده این جمعیت دوبرابر خواهد شد و نرخ سالمندی به 10 درصد برسد [4]. با افزایش سن و آغاز سالمندی، افراد بهتدریج برخی از کارکردهای فیزیولوژیک و روانیاجتماعی خود را از دست میدهند. محرومیت از فعالیتهای اجتماعی، سالمندان را برای ابتلا به افسردگی مستعد میکند و سبب افزایش احساس تنهایی در آنها میشود [5].

احساس تنهایی به صورت وضعیت روانی ناتوانکننده [6] و نارسایی و ضعف محسوس در روابط بینفردی [7] توصیف میشود که نتیجه آن احساس غمگینی، پوچی، تأسف و حسرت است [8]. در واقع احساس تنهایی ناتوانی در برقراری و حفظ روابط رضایتبخش با دیگران است که باعث تجربه حس محرومیت میشود [9]. شواهد نشان میدهند که احساس تنهایی پدیدهای گسترده و فراگیر است و 25 تا 50 درصد کل جمعیت بیش از 65 سال آن را تجربه میکنند [10]. همچنین احساس تنهایی بین سالمندان ساکن آسایشگاه بیش از سالمندانی که با اعضای خانواده زندگی میکنند، گزارش شده است [12 ،11].

پژوهشهای انجامشده در خصوص ارتباط احساس تنهایی و سلامت جسمی و روانی نشان میدهند که احساس تنهایی جنبههای گوناگون زندگی اجتماعی افراد را تحت تأثیر قرار میدهد [13]. احساس تنهایی باعث زوال عقل [14] و رفتار و افکار خودکشیگرا [15] میشود و پیشبینیکننده علائم افسردگی است [17 ،16]. احساس تنهایی در دوره سالمندی در اثر کمبود روابط اجتماعی ایجاد میشود و این سالمندان را برای ابتلا به افسردگی مستعد میکند [5]. در واقع احساس تنهایی و افسردگی حالتهای ناخوشایند و آزارندهای هستند که با هم همپوشی دارند، اما وایس [18] بین آنها تمایز قائل میشود. او احساس تنهایی را به عنوان اینکه احساس مردم درباره روابط اجتماعی خودشان، به طور خاص چگونه هست و افسردگی را به عنوان اینکه احساس مردم به طور کلی چگونه است، تعریف میکند. افسردگی یکی از اختلالات شایع روانپزشکی در سالمندان است [19]. تحقیقات نشان دادهاند که افسردگی سالمندان در آسایشگاه شایع است [21 ،20]. سیک و مالو [22] در مطالعه خود دریافتند که سالمندان با اختلالات خلقی نظیر افسردگی و اضطراب، بالاترین درجه احساس تنهایی را دارند.

باتوجه به اینکه پاسخهای عاطفی افراد تحت تأثیر شناختشان است [23] و از آنجا که بسیاری از افراد با سبک تفکرشان با دیگران ارتباط برقرار میکنند [24]، این موضوع میتواند به تعصب در ارزیابی و قضاوت درباره رویدادها و مسائلی به دلیل تحریفهای شناختی منجر شود [25]. نظریه شناختی مشکلات روانی را ناشی از فرایندهایی چون تفکر معیوب، استنباطهای غلط بر پایه اطلاعات ناکافی یا نادرست و ناتوانی در متمایزکردن خیال از واقعیت میداند. افسردگی نیز به عنوان یکی از مشکلات شناختی به دلیل تعبیر سوگیریشده رویدادها از سوی فرد شکل میگیرد [26].

تحریفهای شناختی افکار و ایدههای نادرستی هستند که موجب فکر منفی و نگهداشتن احساسات منفی میشوند [27] یکی از تحریفات شناختی بسیار مهم، تفکر قطعینگراست [28].در این نوع تفکر، فرد رویدادی را به طور قطعی برابر با چیز دیگری در نظر میگیرد [29]. برای مثال فردی که در آزمون کنکور رد شده است، این رویداد را برابر با بدبختی تفسیر میکند و هر نوع احتمال دیگر را نادیده میگیرد. بنابراین میتوان گفت که تحریف شناختی تفکر قطعینگر که در اثر انعطافناپذیری شناختی در ذهن ظاهر میشود، یکی از دلایل مهم افسردگی و دیگر ناسازگاریهای روانی است [30]. در واقع تفکر قطعینگر میتواند ریشه احساس ناامیدی و درماندگی باشد که باعث دیدگاه منفی به خود و آینده میشود [25]. اعتقاد بر این است حذف این تحریفات و افکار منفی منجر به بهبود خلقوخو و کاهش شدت اختلالاتی از قبیل افسردگی و اضطراب مزمن میشود [31].

مطالعات نشان میدهد که تفکر قطعینگر رابطه نزدیکی با دیگر متغیرهای روانی از جمله افسردگی و رضایت زناشویی [32]، افسردگی [33]، سلامت روان [34]، مهارتهای ارتباطی [35]، امید به زندگی [36] و اضطراب [34] دارد. از این رو تفکر قطعینگر بیشتر در افراد، با انزوای اجتماعی و افسردگی بیشتری همراه است و از طرف دیگر مهارتهای ارتباطی و امید به زندگی کمتری را پیشبینی میکند. وجود روایی همگرا بین پرسشنامه تفکر قطعی و پرسشنامه افسردگی و ارتباط مثبت بین این دو متغییر نیز پیشبینی افسردگی از روی تفکر قطعینگر را بیشتر میسر می کند [27].

اعتبار فرم موازی مقیاس احساس تنهایی با مقیاس افسردگی بک آزموده شده است که ضریب همبستگی 77/0 به دست آمده است که نشان از همبستگی بالای این دو متغیر دارد [37]؛ چنانکه همپوشی بین احساس تنهایی و افسردگی در تحقیقات مختلف هم نشان داده شده است [22 ،5]. اما در هیچیک از تحقیقات مستقیماً به نقش تفکر قطعینگر در پیشبینی افسردگی و احساس تنهایی، آن هم در جامعه سالمندان که مشکلات شناختی در آنها زیاد است، پرداخته نشده است. بنابراین با توجه به نقش تفکر قطعینگر به عنوان عاملی مهم در ایجاد مشکلات شناختی و برداشت منفی از خود و جهان و آینده و با توجه به شایعبودن احساس تنهایی و افسردگی در سالمندان ساکن در آسایشگاه و نیز به دلیل بیتوجهی متخصصان حوزه روانشناسی و مشاوره به نقش این متغیرها در ایجاد مشکلات روانشناختی همچون ناامیدی، تفکر معیوب و انزوای اجتماعی، هدف مطالعه حاضر رابطه تفکر قطعینگر با افسردگی و احساس تنهایی سالمندان است. به عبارت دیگر پژوهش حاضر به دنبال این است که آیا بر اساس تفکر قطعینگر میتوان احساس تنهایی و افسردگی را در سالمندان پیشبینی کرد یا نه.

روش مطالعه

پژوهش حاضر از نوع توصیفیهمبستگی است و جامعه آماری آن شامل تمامی سالمندان زن و مرد بیش از 60 سال ساکن در آسایشگاه سالمندان کهریزک کرج در سال 94-1393 بود که از این بین تعداد 142 نفر سالمند (79 زن و 63 مرد) برای نمونه از طریق روش نمونهگیری در دسترس انتخاب شدند. معیارهای ورود به مطالعه شامل سالمندانی بود که در مدت انجام پژوهش جزو جمعیت مراقبتشده بودند و پرونده داشتند. معیارهای خروج نیز شامل انتقال آنها از یک منطقه جغرافیایی به منطقه دیگر و مرگومیر بود.

ابزارهای استفادهشده در این پژوهش پرسشنامههای مقیاس افسردگی سالمندان (GDS)، مقیاس احساس تنهایی راسل (UCLA) و مقیاس تفکر قطعینگر [28] بود.

برای بررسی وضعیت افسردگی سالمندان، از شکل کوتاه مقیاس افسردگی سالمندان (GDS) برگرفته از فرم 30 سؤالی [38]، استفاده شده است. در سال 1986، شییخ و یاساواگی این پرسشنامه را ساختند [39]. از 15سؤال تشکیل شده است که پاسخ به هر سؤال با بله و خیر مشخص میشود و گروه تحت بررسی را به سه گروه با افسردگی متوسط (5 تا10)، افسردگی شدید (10 تا 15) و فرد سالم تقسیم میکند. این مقیاس روی 204 سالمند ایرانی هنجاریابی شده است، طوری که آلفای کرونباخ 90/0، ضریب همبستگی به روش بازآزمون پس از دو هفته 58/0، در بهترین نقطه برش 8 (حساسیت 9/0، ویژگی 84/0) به دست آمد [40]. در پژوهشی متاآنالیز که در نهایت 17 پژوهش (10 پژوهش GDS15 سؤالی و 7 پژوهش GDS30 سؤالی) تحلیل شدند، نشان داده شد که GDS15 سؤالی با حساسیت3/81 و ویژگی 4/78 نسبت به GDS30 سؤالی با حساسیت 4/77 و ویژگی 4/65 به عنوان ابزار کاربردی بالینی بهتر تشخیص داده شد [41]

مقیاس احساس تنهایی

راسل و همکارانش در سال 1978 برای ارزیابی تنهایی نسخه اصلی مقیاس احساس تنهایی 20 سؤالی را از دانشگاه کالیفرنیا، لسآنجلس (UCLA) توسعه دادند [42]. تمام سؤالهای نسخه اصلی این مقیاس به صورت منفی بود. نسخه تجدیدنظرشده (نسخه دوم) آن در سال 1980، شامل 10 عبارت مثبت و 10 عبارت منفی میشد که باز مشکلاتی در ساختار جملات داشت [43] و در نهایت نسخه تجدیدنظرشده نهایی (نسخه سوم) در سال 1996 که در پژوهش ما هم این نسخه استفاده شده است، 11 عبارت مثبت و 9 عبارت منفی داشت که پاسخ به سؤالات با بیان منفی بر مبنای لیکرت چهاردرجهای شامل هرگز (1)، بهندرت (2)، گاهی اوقات (3) و اغلب (4) است. در ضمن سؤالات با بیان مثبت برعکس نمرهگذاری میشود. طیف نمرات این مقیاس از 20 تا 80 است که نمره 20 نشاندهنده بدون احساس تنهایی و بیشتر از آن نشاندهنده احساس تنهایی است، اما معمولاً نمرات بیشتر از 40 به عنوان احساس تنهایی قلمداد میشود [44]. ضریب پایایی این مقیاس با استفاده از روش آزمون مجدد 94/0 به دست آمده است و ضریب پایایی آلفای کرونباخ این مقیاس 96/0 بهدست آمده است. اعتبار فرم موازی این مقیاس با مقیاس افسردگی بک آزموده شده است که ضریب همبستگی 77/0 به دست آمده است [37].

مقیاس تفکر قطعینگر

این پرسشنامه بر پایه مبانی نظری مربوط به نظریههای شناختی [45 ،28] و نیز تجارب بالینی توسعه داده شد [46]. این پرسشنامه 36 سؤال دارد که با مقیاس لیکرت (نمره 1 برای گزینه کاملاً موافقم تا نمره 4 برای گزینه کاملاً مخالفم) نمرهگذاری میشود. دامنه نمرات در این آزمون بین 36 و 144 است. بدین ترتیب هرچه نمره فرد در مقیاس بالاتر باشد، نشانگر میزان قطعینگری بیشتر در تفکر است. این آزمون روایی و اعتبار مناسبی دارد [45]. همبستگی آزمون افسردگی بک و تفکر قطعینگر و میزان روایی همگرایی آنها 33/0 بوده است. آلفای کرونباخ برای سنجش پایایی درونی آزمون82/0 و برای پایایی در طول زمان از طریق بازآزمایی در فاصله یک هفته 87/0 به دست آمده است. نقطه برش این آزمون نیز برابر با 75 است. از طریق تحلیل عاملی، 5 عامل در این نوع تفکر مشاهده شد که شامل تفکر قطعینگر کلی (9 بخش)، تفکر قطعینگر در رابطه با دیگران (8 بخش)، مطلقنگری فلسفی (7 بخش)، تفکر قطعینگر در پیشبینی آینده (6 بخش) و تفکر قطعی در رویدادهای منفی (6 آیتم) میشود [27].

روش اجرا

با توجه به سالمندان حاضر در آسایشگاه که برخی از آنها به صورت شبانهروزی و برخی نیز فقط روزانه در آنجا بودند و با توجه به معیارهای ورودوخروج، 142 نفر سالمند (63 مرد و 79 زن) برای نمونه پژوهش به صورت در دسترس انتخاب شدند. بعد از ورود افراد به مطالعه مراحل مصاحبه و توزیع پرسشنامه با سالمندان انجام شد. از ملاحظات اخلاقی این پژوهش میتوان به این نکته اشاره کرد که برای تمامی آزمودنیها هریک از موارد ماهیت، هدف و محرمانهبودن نتایج توضیح داده شد، به این معنا که نام و هویت و اطلاعات افراد گروه محرمانه باقی خواهد ماند. نتایج بهدستآمده با کسب رضایت از تکتک افراد شرکتکننده در اختیار افراد و نهادها قرار خواهد گرفت.

یافتهها

دادههای پرسشنامه برای تجزیهوتحلیل وارد نرمافزار AMOS و با استفاده از تحلیل مسیر، تحلیل شدند. تحلیل مسیر نوعی از مدل معادلات ساختاری محسوب میشود که فقط شامل مدل علّی ساختار است. در واقع تحلیل مسیر فقط بر روی متغیرهای مشاهدهشده قابل انجام است. مسیر در مدل علّی نشاندهنده اثر یک متغیر بر متغیر دیگر است. تحلیل مسیر در این پژوهش، مسیر را با فلشی جهتدار یکطرفه که از متغیر برونزا (تفکر قطعینگر) به متغیرهای مربوطه درونزا (افسردگی و احساس تنهایی) رسم شده است، نمایش داده است. در این بخش ابتدا یافتههای توصیفی ارائه شده است که در آن نمایی از مشخصات سالمندان شرکتکننده در این پژوهش ارائه میشود. سپس دادههای جمعآوریشده با استفاده از آمار استنباطی به منظور آزمون فرضیههای پژوهش تحلیل شدند.

طبق نتایج جدول شماره 2 احساس تنهایی و افسردگی در سطح 01/0 رابطه مثبت و معنیداری با تفکر قطعینگر در سالمندان دارد. همچنین در پژوهش حاضر طبق آنچه نتایج جدول شماره 2 نشان میدهد، افسردگی و احساس تنهایی نیز در سطح 05/0 رابطه مثبت و معنیداری در افراد سالمند دارند.

بر اساس نتایج بهدستآمده از آزمون مدل مسیر تحت نرمافزار AMOS مهمترین شاخصهای برازش مدل تحقیق شامل مجذور خیدو (332/0)، درجه آزادی (1)، کای اسکوئر بهنجارشده (332/0)، شاخص نیکویی برازش (998/0) شاخص برازش تطبیقی (999/0) و ریشه میانگین مربعات خطای برآورد (000/0) است. بنابراین مدل تدوینشده مناسب و به اصلاح مدل نیازی نیست.

به طور کلی با استفاده از سطر اول جدول شماره 3، میتوان

از طرف دیگر با توجه به تصویر شماره 1، مشاهده میشود که متغیر مستقل تفکر قطعینگر به میزان 7 درصد تبیینکننده متغیر وابسته احساس تنهایی و نیز به میزان 8 درصد تبیینکننده متغیر وابسته افسردگی در سالمندان بالای 60 سال ساکن در آسایشگاه سالمندان کرج است. بنابراین میتوان ادعا کرد که با اطمینان 99/0 سؤال تحقیق تأیید میشود؛ به این معنی که تفکر قطعینگر پیشبینیکننده افسردگی و احساس تنهایی در سالمندان است.

بحث

هدف پژوهش حاضر بررسی رابطه بین احساس تنهایی و افسردگی با تفکر قطعینگر در سالمندان بود. یافتههای پژوهش نشان داد که احساس تنهایی رابطه مثبت و معنیداری با تفکر قطعینگر بین سالمندان دارد؛ به این معنی که هر چقدر سالمندان با احتمال بیشتری رویدادها و اتفاقات را به طور قطع پیشبینی کنند، احتمال دارد که بیشتر احساس تنهایی کنند.

در تبیین نتایج این قسمت از پژوهش درباره رابطه مثبت و معنیدار احساس تنهایی با تفکر قطعینگر میتوان گفت که تغییرات جسمی در سالمندی که با تغییراتی در ظاهر بدن همراه است، سبب بروز اختلالاتی در تصور فرد از خود میشود که گاه به ایجاد احساس حقارت و بیکفایتی در سالمند منجر میشود و باعث محدودشدن ارتباطات او با دیگران میشود [47]. احساس تنهایی علاوه بر اینکه بر عنصر عاطفی تأکید میکند، بر عنصر شناختی نیز تأکید میکند. به این صورت که احساس تنهایی ناشی از این ادراک است که ارتباطات اجتماعی فرد، برخی از انتظارات او را برآورده نمیکند [48]. یافتههای پژوهشی مؤید آن است که احساس تنهایی یک عامل سببشناختی در سلامت و بهزیستی جمعیتهای گوناگون است و پیامدهای آنی و درازمدت جدی در بهداشت روان دارد [9]. از طرف دیگر، انسان با نیاز به ارتباط و صمیمیت متولد میشود، ولی تفاوتهای فردی در شدت نیاز به تعلقداشتن و چگونگی برآوردن آن مؤثر است، ارضای این نیاز مستلزم تعاملات مثبت و زیاد با افراد دیگر در موقعیت باثباتی است که به شادکامی دوطرف منجر میشود. بنابراین افرادی که در برقراری و حفظ روابط رضایتبخش با دیگران ناتوان هستند و در نتیجه در برآوردن نیاز به تعلق مشکل دارند، احتمالاً حس محرومیتی را تجربه میکنند که با احساس تنهایی نشان داده میشود [49]. با توجه به اینکه سبک تفکر افراد در برقراری ارتباط با دیگران نقش بسزایی ایفا میکند [24]، این موضوع میتواند منجر به تعصب در ارزیابی و قضاوت درباره رویدادها و مسائلی به دلیل تحریفهای شناختی شود [25]. این خود با توجه به شرایطی که از لحاظ جسمی و روانی بر زندگی سالمندان حاکم است، برقراری روابط معنیدار با افراد دیگر دچار خدشه میشود که در نهایت به احساس تنهایی در این افراد منجر میشود. پژوهشهای مختلفی که در زمینه تفکر قطعینگر انجام شده است، این موضوع را تأیید میکند که از آن جمله میتوان به تحقیقات یونسی و همکاران [34]، مقصودزاده [35] و گرتنر [33] اشاره کرد.

یافتههای دیگر پژوهش نشان داد که افسردگی نیز رابطه مثبت و معنیداری با تفکر قطعینگر بین سالمندان دارد. به این معنی که چون سالمندان معمولاً رویدادها و اتفاقات را حتمی میدانند، احتمال اینکه دیدگاه منفی به خود، جهان و آینده پیدا کنند، بیشتر است. این یافتهها با پژوهشهای یونسی و بهرانی [32] مبنی بر همبستگی بین تفکر قطعینگر، افسردگی و رضایت زناشویی همخوانی دارد. در پژوهشی که آنها انجام دادند، به این نتیجه رسیدند که تحریف شناختی تفکر قطعینگر یکی از مؤلفههای ایجادکننده افسردگی و پیشبینیکننده میزان کاهش رضایتمندی زناشویی است. در پژوهشی دیگر گرتنر [33] به این نتیجه رسید که تحریف شناختی تفکر قطعینگر یکی از عوامل ایجادکننده افسردگی است. همچنین این یافتهها با پژوهش یونسی و همکارن [34] نیز همسو بود. آنها به این نتیجه رسیدند که همبستگی منفی بین تفکر قطعینگر با سلامت عمومی و هبستگی مثبتی بین تفکر قطعینگر و اضطراب وجود دارد.

در تبیین نتایج مذکور درباره رابطه مثبت و معنیدار افسردگی با تفکر قطعینگر میتوان گفت که در دیدگاه آسیبشناسی روانی، به نظر میرسد شیوهای که افراد درباره خود و دنیای اطرافشان فکر میکنند، تفاوت عمدهای در سطح آسیبپذیری آنها به استرس، اضطراب و افسردگی ایجاد میکند [24]. بر اساس دیدگاه شناختی بک، شناختهای نادرستی که تحریف شناختی نامیده میشوند، شامل ایدهها و افکار نادرستی است که به تفکر منفی و تداوم عواطف منفی منجر میشود. بسیاری از تحریفهای شناختی نقش عمدهای در ایجاد افسردگی دارند [31]. یکی از تحریفهای شناختی اصلی تفکر قطعینگری است که این نوع تفکر به عنوان ایجادکننده انعطافناپذیری شناختی، یکی از دلایل اصلی برای افسردگی و دیگر ناسازگاریهای روانی است [50].

همچنین نتایج تحلیل مسیر برای بررسی تأثیر تفکر قطعینگر روی هریک از متغیرهای احساس تنهایی و افسردگی نشان داد که تفکر قطعینگر برای پیشبینی افسردگی و احساس تنهایی بین سالمندان ضرایب استاندارد معنیداری دارد. به عبارت دیگر نتایج پژوهش بیانگر پیشبینی افسردگی و احساس تنهایی از روی متغیر تفکر قطعینگر است. به این معنی که سالمندانی که نمره آنها در تفکر قطعینگر بیشتر است، بیشتر احساس تنهایی میکنند و بیشتر احتمال دارد که دچار افسردگی شوند. در تبیین این قسمت از نتایج باید گفت که تفکر قطعینگری به عنوان مادر تحریفهای شناختی روی سلامت روان افراد تأثیر نامطلوبی میگذارد، مثلاً فردی که همسر خود را از دست داده است، فوت همسر را مساوی با بدبختی میداند. چنین فردی و افراد با سطح قطعینگری زیاد، این موقعیتها را به تمام موقعیتهای زندگیشان تعمیم میدهند، در نتیجه دیدگاه فرد به خود، دیگران و آینده را تحت تأثیر قرار میگیرد و او را بیشتر در مرداب افسردگی قرار میدهد. با توجه به رابطه مستقیم افسردگی با احساس تنهایی چنین فردی در اجتماع بیشتر در انزوا فرو میرود و احساس تنهایی خواهد کرد. چون این فرد با توجه به تحریفی که در شناخت او حاصل شده است، آسیبپذیریش به تنیدگیهای روانی بیشتر خواهد بود.

از جمله محدودیتهای پژوهش حاضر سواد کافی نداشتن بعضی از سالمندان ساکن در آسایشگاه بود که این خود میتواند روی نتایج تحقیق اثر بگذارد. شایان ذکر است از آنجا که در تحقیق حاضر از روش نمونهگیری در دسترس استفاده شده است، در تعمیم نتایج آن باید جانب احتیاط رعایت شود.

با توجه به نتایج حاصلشده، پیشنهاد میشود که در کلینیکهای روانشناسی و مشاوره از یافتههای این پژوهش برای آگاهسازی افراد برای مقابله با تفکر قطعینگر و بهتبع پیشگیری یا کاهش مشکلات سلامت روان از جمله افسردگی، احساس تنهایی و دیگر متغیرهای آسیبرسان روانشناختی استفاده کرد. برای پیشنهاد پژوهشی، نقش تفکر قطعینگر با دیگر متغیرهای بهداشت روان از جمله ناامیدی و درماندگی به عنوان نقاط عطف افسردگی بررسی شوند. همچنین پژوهشهایی در راستای این پژوهش در دیگر گروههای سنی و به دیگر روشهای نمونهگیری از جمله روش نمونهگیری خوشهای به کار گرفته شود.

نتیجهگیری نهایی

با توجه به یافتهها میتوان نتیجه گرفت که زیادی تفکر قطعینگر میتواند افسردگی و احساس تنهایی را در سالمندان پیشبینی کند. هرچه افراد حوادث را با قطعیت پیشبینی کنند بیشتر مستعد فرورفتن در احساسات تنهایی و افسردگی هستند.

تشکر و قدردانی

از تمامی سالمندان و مسئولان آسایشگاه که در این پژوهش نهایت همکاری را با پژوهشگران کردند، کمال تشکر و قدردانی را داریم. این مقاله حامی مالی ندارد.

[1]Salar A, Boryri T, Khojasteh F, Salar E, Jafari H, Karimi M. [Evaluating the physical, psychological and social problems and their relation to demographic factors among the elderly in Zahedan city during 2010-2012 (Persian)]. Feyz Journals of Kashan University of Medical Sciences. 2013; 17(3): 305-311.

[2]Payahoo L, Khaje-bishak Y, Pourghasem B, Kabir-alavi M-b. [The survey of the relationship between quality of life of elderly with depression and physical activity in Tabriz, Iran (Persian)]. Rehabilitation Medicine. 2014; 2(2):39-46.

[3]Ahmadzadeh GH. [Geriateric depressive disorder (comorbidity of depression with medical conditions in geriatric patients) (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences, 2010; 8(2): 147-158.

[4]Manzouri L, Babak A, Merasi M. [The depression status of the elderly and it’s related factors in Isfahan in 2007 (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2010; 4(4):27-33.

[5]Koochaki G, Hojjati H, Sanagoo A. [The relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction of the elderly in Gorgan and Gonbad Cities (Persian)]. Journal of Research Development in Nursing & Midwifery. 2012; 9(1):61-68

[6]VanderWeele TJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. A marginal structural model analysis for loneliness: Implications for intervention trials and clinical practice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011; 79(2):225–35. doi: 10.1037/a0022610

[7]Parkhurst JT, Hopmeyer A. Developmental change in the sources of loneliness in childhood and adolescence: Constructing a theoretical model. Loneliness in childhood and adolescence. 1999:56-79. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511551888.004

[8]Asher SR, Paquette JA. Loneliness and peer relations in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003; 12(3):75-8. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01233

[9]Heinrich LM, Gullone E. The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006; 26(6):695-718. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

[10]Chiang KJ, Chu H, Chang HJ, Chung MH, Chen CH, Chiou HY, et al. The effects of reminiscence therapy on psychological well-being, depression, and loneliness among the institutionalized aged. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010; 25(4):380-388. doi: 10.1002/gps.2350

[11]Bondevik M, Skogstad A. Loneliness among the oldest old, a comparison between residents living in nursing homes and residents living in the community. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1996; 43(3):181-97. doi: 10.2190/9c14-nhux-xqpl-ga5j

[12]Alpass FM, Neville S. Loneliness, health and depression in older males. Aging & Mental Health. 2003; 7(3):212-6.

[13]Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010; 15(3):219–66. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394

[14]Tilvis RS, Kähönen-Väre MH, Jolkkonen J, Valvanne J, Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE. Predictors of cognitive decline and mortality of aged people over a 10-year period. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2004; 59(3):M268-M274. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m268

[15]Rudatsikira E, Muula AS, Siziya S, Twa-Twa J. Suicidal ideation and associated factors among school-going adolescents in rural Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2007; 7(1):67. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-7-67

[16]Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging. 2006; 21(1):140-51. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140

[17]Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010; 40(2):218-27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

[18]Weiss RS. Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1975.

[19]Davidian H. [Recognizing and treating depression in Iranian culture (Persian)]. Tehran: Iran Academy of Medical Science; 2007.

[20]Rezayi S, Manouchehri M. [Comparison of mental disorders between home owner residents and nurse homes elders (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2008; 3(1):16-25.

[21]Mobasheri M, Moezy M. [The prevalence of depression among the elderly population of Shaystegan and Jahandidegan nursing homes in Shahrekord (Persian)]. Journal of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. 2010; 12(3):89-94.

[22]Theeke LA, Mallow J. Loneliness and quality of life in chronically Ill rural older adults: Findings from a pilot study. American Journal of Nursing. 2013; 113(9):28-37. doi: 10.1097/01.naj.0000434169.53750.14

[23]Somers S. Emotionally reconsidered: The role of cognition in emotional responsiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981; 41(3):553-61. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.41.3.553

[24]Warner R. The environment of schizophrenia: Innovations in practice, policy and communications. Abingdon: Routledge; 2000.

[25]Younesi J, Manzari Tavakkoli V, Hashemzadeh V. Relationship between Deterministic Thinking and Defense Mechanisms among students at University of Tehran. Journal of Behavioral Sciences in Asia. 2014; 2(8):19-31.

[26]Corey G. Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy. Scarborough: Nelson Education; 2015.

[27]Younesi J, Mirafzal AA. Development of deterministic thinking scale based on Iranian culture. Psychology. 2013; 4(11):808-812. doi: 10.4236/psych.2013.411116

[28]Younesi J, Mirafzal A. Development of deterministic thinking questionnaire. Paper presented at: 10th European Congress of Psychology Prague Czech Republic; 3-6 July 2007; Prague, Czech.

[29]Esbati M. The state of Deterministic Thinking among mothers of autistic children. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2011; 9(14):10-13.

[30]Younesi SJ, Mirafzal A, Tooyserkani M. deterministic thinking among cancer patients as a new method to increase psychosocial adjustments. Iranian Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2012; 5(2):81-6. PMCID: PMC4299623

[31]Beck AT, Epstein N, Harrison R. Cognitions, attitudes and personality dimensions in depression. British Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1983; 1:1–16.

[32]Gertner J. The futile pursuit of happiness. The New York Times Magazine. 2003 Sept 7:44-7.

[33]Younesi SJ, Ravari MT, Esbati M. Relationship between Deterministic Thinking and General Health. Applied Psychology. 2014; 2(6):38-47.

[34]Maghsoudzade M. [Prediction of marital satisfaction of Shahed sons and spouses by rate of deterministic thinking and communication skills (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: University of social welfare and rehabilitation sciences; 2010.

[35]Rah Anjam S. [Prediction of hope rate by deterministic thinking among students of Azad universities of Tehran] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Islamic Azad University; 2010.

[36]Daniel K. Loneliness and depression among university Students in Kenya. Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research. 2013; 13(4):11-18.

[37]Yesavage JA, Brink T, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1983; 17(1):37-49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4

[38]Shiekh J, Yesavage J. Geriatric Depression Scale: Recent findings and development of a short version. In: Brink T editor. Clinical gerontology: A guide to assessment and intervention. New York: Howarth Press; 1986.

[39]Malakouti K, Fathollahi P, Mirabzadeh A, Salavati M, Kahani S. [Validation of Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) in Iran (Persian)]. Research in Medicine. 2006; 30(4):361-9.

[40]Mitchell AJ, Bird V, Rizzo M, Meader N. Diagnostic validity and added value of the Geriatric Depression Scale for depression in primary care: A meta-analysis of GDS 30 and GDS 15. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010; 125(1):10-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.019

[41]Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1978; 42(3):290-4. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11

[42]Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980; 39(3):472-80. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472

[43]Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996; 66(1):20-40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

[44]Younesi J. The role of cognitive distortion (Deterministic thinking) on Psychological pathology. Iranian Association of Psychology. 2004; 3(12):73-86.

[45]Younesi J, Younesi M, Asgari A. Prediction of rate of marital satisfaction among Tehranian couples by deterministic thinking. Paper Presented at: The 28th International Congress of Psychology. 8-13 August 2008; Berlin, Germany.

[46]Franklin LL, Ternestedt BM, Nordenfelt L. Views on dignity of elderly nursing home residents. Nursing Ethics. 2006; 13(2):130-46. doi: 10.1191/0969733006ne851oa

[47]Routasalo PE, Savikko N, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE, Pitkälä KH. Social contacts and their relationship to loneliness among aged people–a population-based study. Gerontology. 2006; 52(3):181-7. doi: 10.1159/000091828

[48]Sheikholeslami F, Masouleh SR, Khodadadi N, Yazdani M. [Loneliness and general health of elderly (Persian)]. Holistic Nursing and Midwifery. 2012; 21(2):28-34.

[49]Weishaar ME, Beck AT. Hopelessness and suicide. International Review of Psychiatry. 1992; 4(2):177-84. doi: 10.3109/09540269209066315

Received: 2017/02/13 | Accepted: 2017/06/02 | Published: 2017/10/07

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |