Volume 16, Issue 1 (Spring (COVID-19 and Older Adults) 2021)

Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing 2021, 16(1): 112-127 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Heshmatifar N, Davarinia Motlagh Quchan A, Mohammadzadeh Tabrizi Z, Moayed L, Moradi S, Rastagi S et al . Prevalence and Factors Related to Self-Medication for COVID-19 Prevention in the Elderly. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing 2021; 16 (1) :112-127

URL: http://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2033-en.html

URL: http://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2033-en.html

Narjes Heshmatifar1

, Arezoo Davarinia Motlagh Quchan2

, Arezoo Davarinia Motlagh Quchan2

, Zohreh Mohammadzadeh Tabrizi2

, Zohreh Mohammadzadeh Tabrizi2

, Leila Moayed3

, Leila Moayed3

, Sajad Moradi4

, Sajad Moradi4

, Sedighe Rastagi5

, Sedighe Rastagi5

, Fatemeh Borzooei *6

, Fatemeh Borzooei *6

, Arezoo Davarinia Motlagh Quchan2

, Arezoo Davarinia Motlagh Quchan2

, Zohreh Mohammadzadeh Tabrizi2

, Zohreh Mohammadzadeh Tabrizi2

, Leila Moayed3

, Leila Moayed3

, Sajad Moradi4

, Sajad Moradi4

, Sedighe Rastagi5

, Sedighe Rastagi5

, Fatemeh Borzooei *6

, Fatemeh Borzooei *6

1- Department of Nursing, Aging Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

2- Department of Anesthesiology, Student Research Committee, School of Paramedics, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

3- Department of Geriatric Nursing, School of Nursing, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

4- Vasei Hospital, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran.

5- Department of Biostatistics, Student Research Committee, School of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

6- Department of Operating Room, Aging Research Center, School of Paramedics, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Iran. ,borzoee75026@yahoo.com

2- Department of Anesthesiology, Student Research Committee, School of Paramedics, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

3- Department of Geriatric Nursing, School of Nursing, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

4- Vasei Hospital, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran.

5- Department of Biostatistics, Student Research Committee, School of Health, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

6- Department of Operating Room, Aging Research Center, School of Paramedics, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 6113 kb]

(2476 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6284 Views)

Full-Text: (4171 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

In 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), as a global emergency [1]. All age groups are at risk for coronavirus infection; however, the elderly are more vulnerable for various reasons, including deficits in immune systems, chronic diseases, poor personal hygiene, loneliness, multi drugs use, and the lack of medical attention [2]. Morbidity, mortality, the lack of specific treatment for COVID-19 [3], and psychological problems, like death anxiety, have led the elderly to arbitrarily use drugs [4]. Studies suggested that the elderly lack the necessary knowledge about the adverse effects of self-medication; thus, they must acquire sufficient knowledge to change behavior [5]. Despite the importance of pharmaco-epidemiological studies, such studies were not found in critical conditions. Due to the aging trend of the population of the country, the present study aimed to investigate factors related to the arbitrary use of drugs for COVID-19 prevention in the elderly.

2. Methods and Materials

This descriptive and cross-sectional study was performed on 360 elderly (aged >60 years). Based on self-reported data, the selected elderly had no acute physical or cognitive problems.

The samples were identified by a random cluster sampling method. They were determined from the population areas of 16 comprehensive health centers in Sabzevar City, Iran; the city was divided into 4 regions. Two centers were randomly selected per region. Then, a sample size appropriate to the number of the elderly per center was selected from each center. Given the special conditions of COVID-19 and the impossibility of face-to-face communication, the researcher used the WhatsApp platform to form a group among the elderly; accordingly, the required data were collected remotely. In addition to completing the online questionnaire, the research units were requested to mention the names of the drugs used or to send a picture of the drug package. The questionnaire included a section where informed the elderly that they could leave the study freely.

To collect the necessary data, a demographic form and a researcher-made questionnaire were used. These tools examined the self-medication status of the elderly during the last 3 months in the COVID-19 crisis. The explored elderly’s self-medication status consisted of 21 items, including the history and type of self-medication during the COVID-19 pandemic (4 items), awareness of the type of medication (3 items), self-medication situations (7 items), and medications used to prevent COVID-19 (7 items). The items were answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by the content validity method and its face validity was also approved as desirable. The reliability of the questionnaire was determined by the internal consistency reliability method and its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was measured as 89%. Descriptive statistics and Chi-squared test were used to evaluate self-medication and qualitative variables. The obtained data were analyzed using SPSS at a significance level of 0.05. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MEDSAB.REC.1399.020).

The samples were identified by a random cluster sampling method. They were determined from the population areas of 16 comprehensive health centers in Sabzevar City, Iran; the city was divided into 4 regions. Two centers were randomly selected per region. Then, a sample size appropriate to the number of the elderly per center was selected from each center. Given the special conditions of COVID-19 and the impossibility of face-to-face communication, the researcher used the WhatsApp platform to form a group among the elderly; accordingly, the required data were collected remotely. In addition to completing the online questionnaire, the research units were requested to mention the names of the drugs used or to send a picture of the drug package. The questionnaire included a section where informed the elderly that they could leave the study freely.

To collect the necessary data, a demographic form and a researcher-made questionnaire were used. These tools examined the self-medication status of the elderly during the last 3 months in the COVID-19 crisis. The explored elderly’s self-medication status consisted of 21 items, including the history and type of self-medication during the COVID-19 pandemic (4 items), awareness of the type of medication (3 items), self-medication situations (7 items), and medications used to prevent COVID-19 (7 items). The items were answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by the content validity method and its face validity was also approved as desirable. The reliability of the questionnaire was determined by the internal consistency reliability method and its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was measured as 89%. Descriptive statistics and Chi-squared test were used to evaluate self-medication and qualitative variables. The obtained data were analyzed using SPSS at a significance level of 0.05. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MEDSAB.REC.1399.020).

3. Results

The study sample included 152(44.5%) males and 190(55.5%) females; the Mean±SD age of the study participants was 66.2±5.67 years. Moreover, 57.3% of the study samples were married and 42.7% were single. Furthermore, 29.8% of the study participants were illiterate, 54.5% had an elementary education, and 15.7% had a high school diploma or higher. Besides, 31.3% of the study samples were retired, 21.6% were self-employed, and 47.3% were unemployed. Additionally, 30.4% of the study subjects used no health insurance, 52.7% used regular insurance, and 16.9% used supplementary insurance.

The Chi-square test data indicated a significant relationship between self-medication, and education and insurance coverage (P<0.05). However, this test presented a significant relationship between gender, occupation, and marital status, and self-medication (P>0.05).

The collected results revealed that the rate of arbitrary drug use during the COVID-19 pandemic in the elderly equaled 193(56.4%). Despite self-medication in more than 50% of units of this study, only 13.3% of them had the minimum necessary drug information (drug name, classification, uses, & adverse effects). Moreover, 53.8% of the research units provided drugs from home and 46.2% from pharmacies. Furthermore, 98(50.7%) of the explored elderly used drugs in the form of tablets or capsules, 25.3% used syrups, 11.9% used ampoules, and 11.9% used other forms of drugs. The type of knowledge of most of them about self-medication based on the category of drugs was 39.1%; the same rate for sending a package photo of the drugs was 37.7%, and 23.2% of the samples mentioned the name of the drug used.

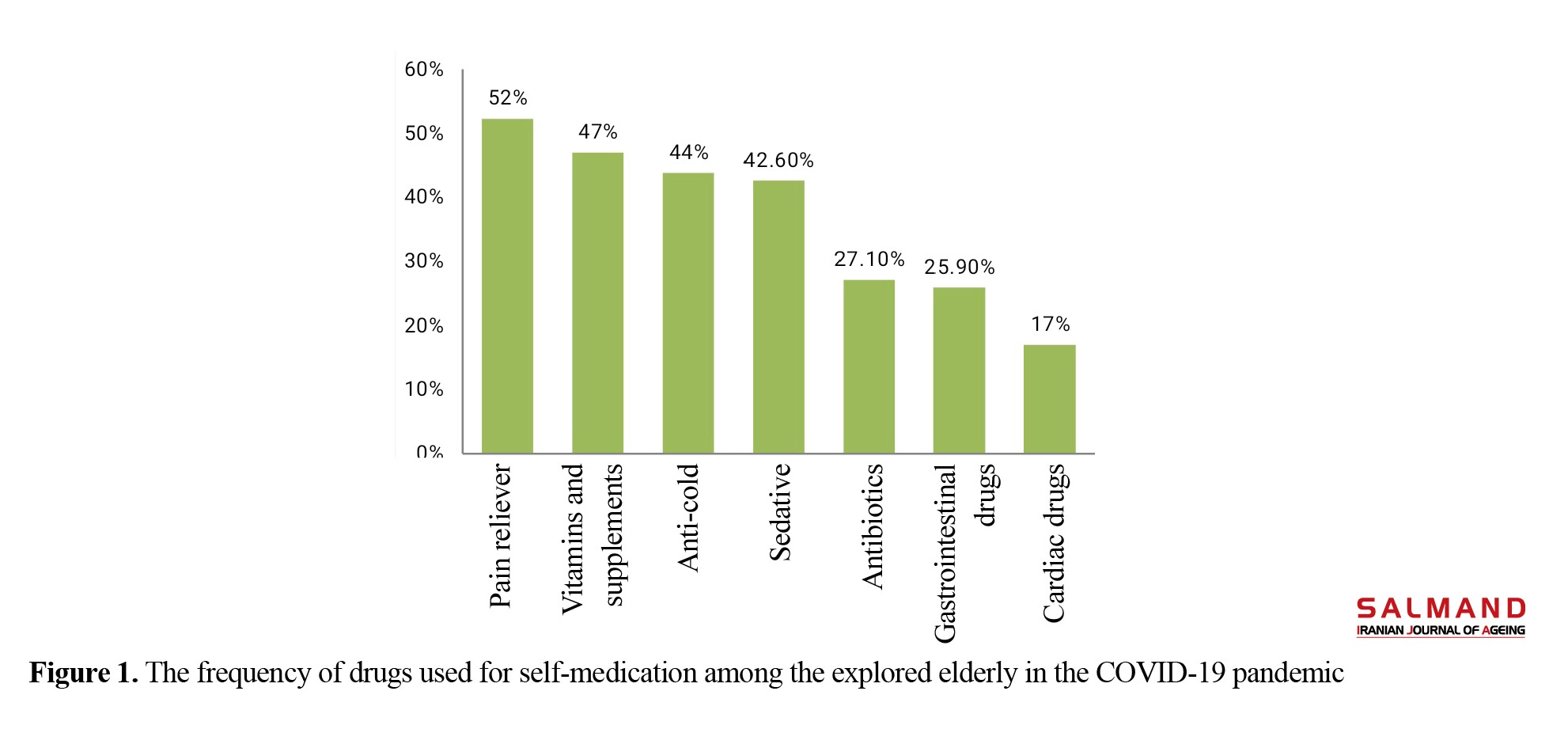

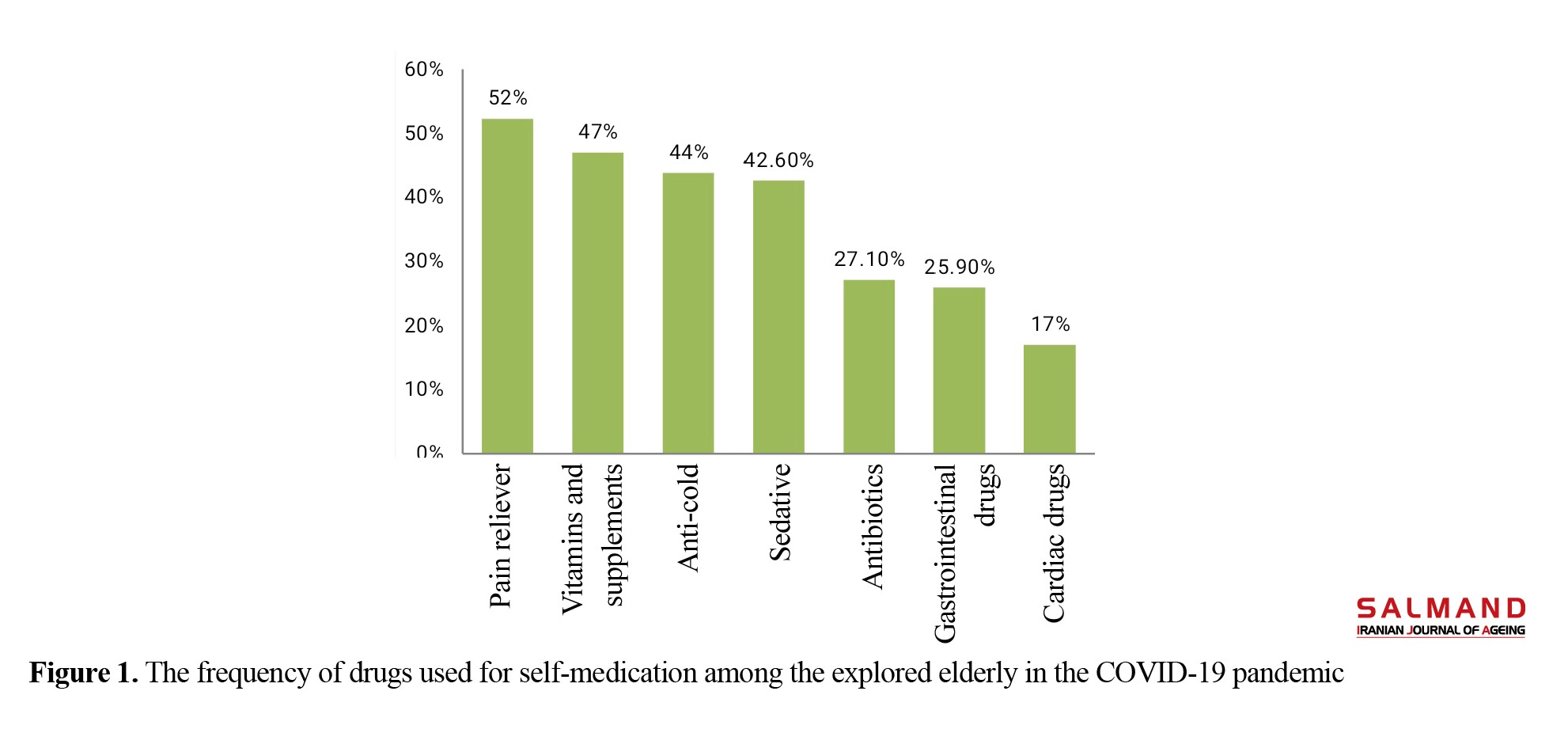

In evaluating the conditions and situations of self-medication in the examined elderly, 43.4% related to joint and muscle pain, 42% neurological diseases, 41.9% pseudo-corona symptoms, 31% weakness and lethargy, and 21% headache. The prevalence of gastrointestinal conditions and cardiovascular disorders were 20% and 12% in the study subjects, respectively. The highest drug classes in arbitrary use in the research units were analgesics, tonics, anti-colds, and sedatives, orderly (Figure 1).

The main reasons for the arbitrary use of the drug during the COVOD-19 pandemic in the elderly who reported self-medication respectively concerned COVID-19 prevention, as the most common cause (52%), followed by self-medication for other reasons, such as home quarantine and avoiding going out, not affording a physician visit, previous experience in the use of drugs, and others’ advice (Table 1).

.jpg)

The Chi-square test data indicated a significant relationship between self-medication, and education and insurance coverage (P<0.05). However, this test presented a significant relationship between gender, occupation, and marital status, and self-medication (P>0.05).

The collected results revealed that the rate of arbitrary drug use during the COVID-19 pandemic in the elderly equaled 193(56.4%). Despite self-medication in more than 50% of units of this study, only 13.3% of them had the minimum necessary drug information (drug name, classification, uses, & adverse effects). Moreover, 53.8% of the research units provided drugs from home and 46.2% from pharmacies. Furthermore, 98(50.7%) of the explored elderly used drugs in the form of tablets or capsules, 25.3% used syrups, 11.9% used ampoules, and 11.9% used other forms of drugs. The type of knowledge of most of them about self-medication based on the category of drugs was 39.1%; the same rate for sending a package photo of the drugs was 37.7%, and 23.2% of the samples mentioned the name of the drug used.

In evaluating the conditions and situations of self-medication in the examined elderly, 43.4% related to joint and muscle pain, 42% neurological diseases, 41.9% pseudo-corona symptoms, 31% weakness and lethargy, and 21% headache. The prevalence of gastrointestinal conditions and cardiovascular disorders were 20% and 12% in the study subjects, respectively. The highest drug classes in arbitrary use in the research units were analgesics, tonics, anti-colds, and sedatives, orderly (Figure 1).

The main reasons for the arbitrary use of the drug during the COVOD-19 pandemic in the elderly who reported self-medication respectively concerned COVID-19 prevention, as the most common cause (52%), followed by self-medication for other reasons, such as home quarantine and avoiding going out, not affording a physician visit, previous experience in the use of drugs, and others’ advice (Table 1).

.jpg)

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The present study results suggested that approximately 1.2 of the explored elderly practiced self-medication during the COVID-19 pandemic; thus, they felt at risk of contracting the coronavirus. Reducing the fear of the elderly by raising awareness and providing accurate information about COVID-19 is essential by creating a campaign in public and virtual media. Self-medication has also been reported in the educated and uninsured elderly. It is recommended that those in charge of drug supply take all considerations, including refraining from dispensing over-the-counter drugs and providing training on the arbitrary use of drugs in old age when purchasing drugs. Due to the possible problems and risks due to arbitrary drug use in the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems necessary to provide special training programs for the elderly in healthcare centers. Therefore, it is recommended that the authorities take action to reduce this problem to raise the elderly’s awareness.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MEDSAB.REC.1399.020). All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This study was extracted from a research project of Nursing School from Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, writing – review & editing: Narjes Heshmatifar, Fatemeh Borzoee; Methodology, review: Arezoo Davarinia Motlagh Quchan, Zohreh Mohammadzadeh Tabrizi, Sajad Moradi; Data collection: Leila Moayed; Data analysis: Sedighe Rastaghi.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all staff and officials in Sabzevar School of Nursing and health centers in Sabzevar are thanked.

Reference

- Locquet M, Honvo G, Rabenda V, Van Hees T, Petermans J, Reginster JY, et al. Adverse health events related to self-medication practices among elderly: A systematic review. Drugs & Aging. 2017; 34(5):359-65. [DOI:10.1007/s40266-017-0445-y] [PMID]

- Montastruc JL, Bondon-Guitton E, Abadie D, Lacroix I, Berreni A, Pugnet G, et al. Pharmacovigilance, risks and adverse effects of self-medication. Therapies. 2016; 71(2):257-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.therap.2016.02.012] [PMID]

- Korani TAT, Darvishporkakhki A, Shahsavari S, Esmaeli R. [Assessment of selfmedication and associated factors among elderly living in Kermanshah city in 2014 (Persian)]. Journal of Geriatric Nursing. 2015; 3(1):38-48. [DOI:10.21859/jgn.3.1.38]

- Chouhan K, Prasad SB. Self-medication and their consequences: A challenge to health professional. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2016; 9(2):314-7. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dr-Shyam-Prasad/publication/302959170_Self-medication_and_their_consequences_A_challenge_to_health_professional/links/5734493908ae298602dcff89/Self-medication-and-their-consequences-A-challenge-to-health-professional.pdf

- Ghorbani M, Ghanei Gheshlagh R, Dalvand S, Moradi B, Faramarzi P, Moradi MZ. [Evaluation of self-medication and related factors in elderly population of Sanandaj, Iran (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedical Faculty. 2019; 4(4):46-57. http://sjnmp.muk.ac.ir/article-1-188-en.html

- Zhang X, Zhou S, Zhou Y, Liu X. [Research progress in inappropriate drug use in the elderly (Chinese)]. Chinese Journal of Geriatrics. 2018; 37(4):479-84. http://wprim.whocc.org.cn/admin/article/articleDetail?WPRIMID=709288&articleId=709773

- Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2014; 13(1):57-65. [DOI:10.1517/14740338.2013.827660] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Shenoy P, Harugeri A. Elderly patients’ participation in clinical trials. Perspectives in Clinical Research. 2015; 6(4):184-9. [DOI:10.4103/2229-3485.167099] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Novel CP. [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China (Chinese)]. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi= Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2020; 41(2):145-51. [DOI:10.46234/ccdcw2020.032]

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2020; 34(5):e212-3. [DOI:10.1111/jdv.16387]

- Tan L, Wang Q, Zhang D, Ding J, Huang Q, Tang YQ, et al. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: A descriptive and predictive study. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2020; 5:33. [DOI:10.1038/s41392-020-0159-1] [PMCID]

- Liu K, Chen Y, Lin R, Han K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: A comparison with young and middle-aged patients. Journal of Infection. 2020; 80(6):e14-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Airagnes G, Pelissolo A, Lavallée M, Flament M, Limosin F. Benzodiazepine misuse in the elderly: Risk factors, consequences, and management. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2016; 18(10):89. [DOI:10.1007/s11920-016-0727-9] [PMID]

- Sundel M, Sundel SS. Behavior change in the human services: Behavioral and cognitive principles and applications. California: Sage Publications; 2017. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/behavior-change-in-the-human-services/book245199

- Ribeiro DC, Milosavljevic S, Abbott JH. Sample size estimation for cluster randomized controlled trials. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2018; 34:108-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.msksp.2017.10.002] [PMID]

- Masumoto S, Sato M, Maeno T, Ichinohe Y, Maeno T. Factors associated with the use of dietary supplements and over-the-counter medications in Japanese elderly patients. BMC Family Practice. 2018; 19:20. [DOI:10.1186/s12875-017-0699-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Niclós G, Olivar T, Rodilla V. Factors associated with self‐medication in Spain: A cross‐sectional study in different age groups. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2018; 26(3):258-66. [DOI:10.1111/ijpp.12387] [PMID]

- Jafari F, Khatony A, Rahmani E. Prevalence of self-medication among the elderly in Kermanshah-Iran. Global Journal of Health Science. 2015; 7(2):360-5. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v7n2p360]

- Gracia-Vásquez SL, Ramírez-Lara E, Camacho-Mora IA, Cantú-Cárdenas LG, Gracia-Vásquez YA, Esquivel-Ferriño PC, et al. An analysis of unused and expired medications in Mexican households. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2015; 37(1):121-6. [DOI:10.1007/s11096-014-0048-1] [PMID]

- Jerez-Roig J, Medeiros LF, Silva VA, Bezerra CL, Cavalcante LA, Piuvezam G, et al. Prevalence of self-medication and associated factors in an elderly population: A systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2014; 31(12):883-96. [DOI:10.1007/s40266-014-0217-x] [PMID]

- Balbuena FR, Aranda AB, Figueras A. Self-medication in older urban mexicans. Drugs & Aging. 2009; 26(1):51-60. [DOI:10.2165/0002512-200926010-00004] [PMID]

- Murphy N, Karlin-Zysman C, Anandan S. Management of chronic pain in the elderly: A review of current and upcoming novel therapeutics. American Journal of Therapeutics. 2018; 25(1): e36-43. [DOI:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000659]

- Rapo-Pylkkö S, Haanpää M, Liira H. Chronic pain among community-dwelling elderly: A population-based clinical study. Scandinavian journal of Primary Health Care. 2016; 34(2):159-64. [DOI:10.3109/02813432.2016.1160628] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020; 323(11):1061-9. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.1585] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020; 395(10223):497-506. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5]

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020; 395(10223):507-13. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7]

- Makowska M, Boguszewki R, Nowakowski M, Podkowińska M. Self-medication-related behaviors and Poland’s COVID-19 lockdown. International journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8344. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17228344] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Onchonga D. A Google Trends study on the interest in self-medication during the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) disease pandemic. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2020; 28(7):903-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2020.06.007] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sadio AJ, Gbeasor-Komlanvi FA, Konu RY, Bakoubayi AW, Tchankoni MK, Bitty-Anderson AM, et al. Assessment of self-medication practices in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak in Togo. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21:58. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-10145-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Quispe-Cañari JF, Fidel-Rosales E, Manrique D, Mascaró-Zan J, Huamán-Castillón KM, Chamorro-Espinoza SE, et al. Self-medication practices during the COVID-19 pandemic among the adult population in Peru: A cross-sectional survey. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2020 ;29(1):1-11. [DOI:10.2139/ssrn.3688689]

- Ocan M, Bwanga F, Bbosa GS, Bagenda D, Waako P, Ogwal-Okeng J, et al. Pattern and predictor of self medication in northern Uganda. Plos One. 2014; 9(3):e92323 [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0092323] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ayalew MB. Self-medication practice in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2017; 11:401-13 [DOI:10.2147/PPA.S131496] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Flett GL, Heisel MJ. Aging and feeling valued versus expendable during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: A review and commentary of why mattering is fundamental to the health and well-being of older adults. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020:1-27. [DOI:10.1007/s11469-020-00339-4]

- Jamhour A, El-Kheir A, Salameh P, Hanna PA, Mansour H. Antibiotic knowledge and self-medication practices in a developing country: A cross-sectional study. American Journal of Infection Control. 2017; 45(4):384-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2016.11.026] [PMID]

- Hem E, stokke G, Cronvold NT. Self- prescribing among young Norwegian doctors: A nine year followup study of a nation with sample. BMC Medicine. 2005; 3:16. [DOI:10.1186/1741-7015-3-16] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

gerontology

Received: 2020/06/07 | Accepted: 2021/01/31 | Published: 2021/04/01

Received: 2020/06/07 | Accepted: 2021/01/31 | Published: 2021/04/01

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |