Volume 16, Issue 1 (Spring (COVID-19 and Older Adults) 2021)

Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing 2021, 16(1): 30-45 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Gholamzad S, Saeidi N, Danesh S, Ranjbar H, Zarei M. Analyzing the Elderly’s Quarantine-related Experiences in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing 2021; 16 (1) :30-45

URL: http://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2143-en.html

URL: http://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2143-en.html

1- Student Research Committee, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Mental Health Research Center, Psychosocial Health Research Institue, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Gerontology, School of Behavioral Science and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,zareii.m@iums.ac.ir

2- Mental Health Research Center, Psychosocial Health Research Institue, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Gerontology, School of Behavioral Science and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 7912 kb]

(3421 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (8484 Views)

Full-Text: (6962 Views)

Extended Abstract

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, coronavirus infection is a global crisis that has seriously endangered public health [1]. According to these statistics, the elderly are considered to be the most vulnerable group of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to their physical condition and vulnerability; they are also the first group to be quarantined [3].

As stated, epidemics can cause various socio-behavioral changes that result from the way individuals experience them. Aging is a critical period of human life; accordingly, paying attention to issues and understanding the needs of this stage is an essential social necessity. Few studies have been conducted on the psychological effects of home quarantine and COVID-19 in Iran; thus, it is necessary to investigate the psychological effects of home quarantine as an emerging phenomenon. Therefore, the present study was conducted with the aim of qualitative analysis of the elderly experiences of quarantine and daily life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As stated, epidemics can cause various socio-behavioral changes that result from the way individuals experience them. Aging is a critical period of human life; accordingly, paying attention to issues and understanding the needs of this stage is an essential social necessity. Few studies have been conducted on the psychological effects of home quarantine and COVID-19 in Iran; thus, it is necessary to investigate the psychological effects of home quarantine as an emerging phenomenon. Therefore, the present study was conducted with the aim of qualitative analysis of the elderly experiences of quarantine and daily life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods and Materials

This qualitative study used a content analysis method. The study population included the elderly who were referred to the clinic of the Faculty of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health of Iran University of Medical Sciences. The sampling method was purposive and the sample size was determined based on data saturation. To conduct this study, a semi-structured interview was conducted. First, the medical records of the elderly referring to the clinic of the Faculty of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the research. Then, they were contacted by phone. While explaining the objectives of the research, a suitable time for the interview was considered. The inclusion criteria were as follows: the elderly aged ≥60 years who provided an informed consent form to participate in the study; as well as the lack of comorbidity of active psychotic disorders, current substance and alcohol use, and cognitive impairments. The exclusion criteria were the patient’s unwillingness to participate in the study at any stage of the study. The interview time lasted between 20 and 45 minutes, depending on the conditions of the study participant and the interview process. After 10 interviews, no new information was added and the analysis was performed on 10 participants.

For data analysis, Maxqda software and Granheim and Landmann content analysis methods were used; they included word-for-word interviews and several times reading the text to develop the general meaning; dividing the text into semantic units summary; the abstraction of semantic units, summarizing and labeling by codes; separating of codes into sub-themes and their comparison based on their similarities and differences, and setting of themes as an indicator of the hidden content of the text [4].

To ensure the accuracy and precision of the research findings in this section, 4 criteria of validity, reliability, transferability, and verification were observed in Lincoln’s and Guba’s qualitative research [5].

The relevant code of ethics was also obtained for this research (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.226).

For data analysis, Maxqda software and Granheim and Landmann content analysis methods were used; they included word-for-word interviews and several times reading the text to develop the general meaning; dividing the text into semantic units summary; the abstraction of semantic units, summarizing and labeling by codes; separating of codes into sub-themes and their comparison based on their similarities and differences, and setting of themes as an indicator of the hidden content of the text [4].

To ensure the accuracy and precision of the research findings in this section, 4 criteria of validity, reliability, transferability, and verification were observed in Lincoln’s and Guba’s qualitative research [5].

The relevant code of ethics was also obtained for this research (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.226).

3. Results

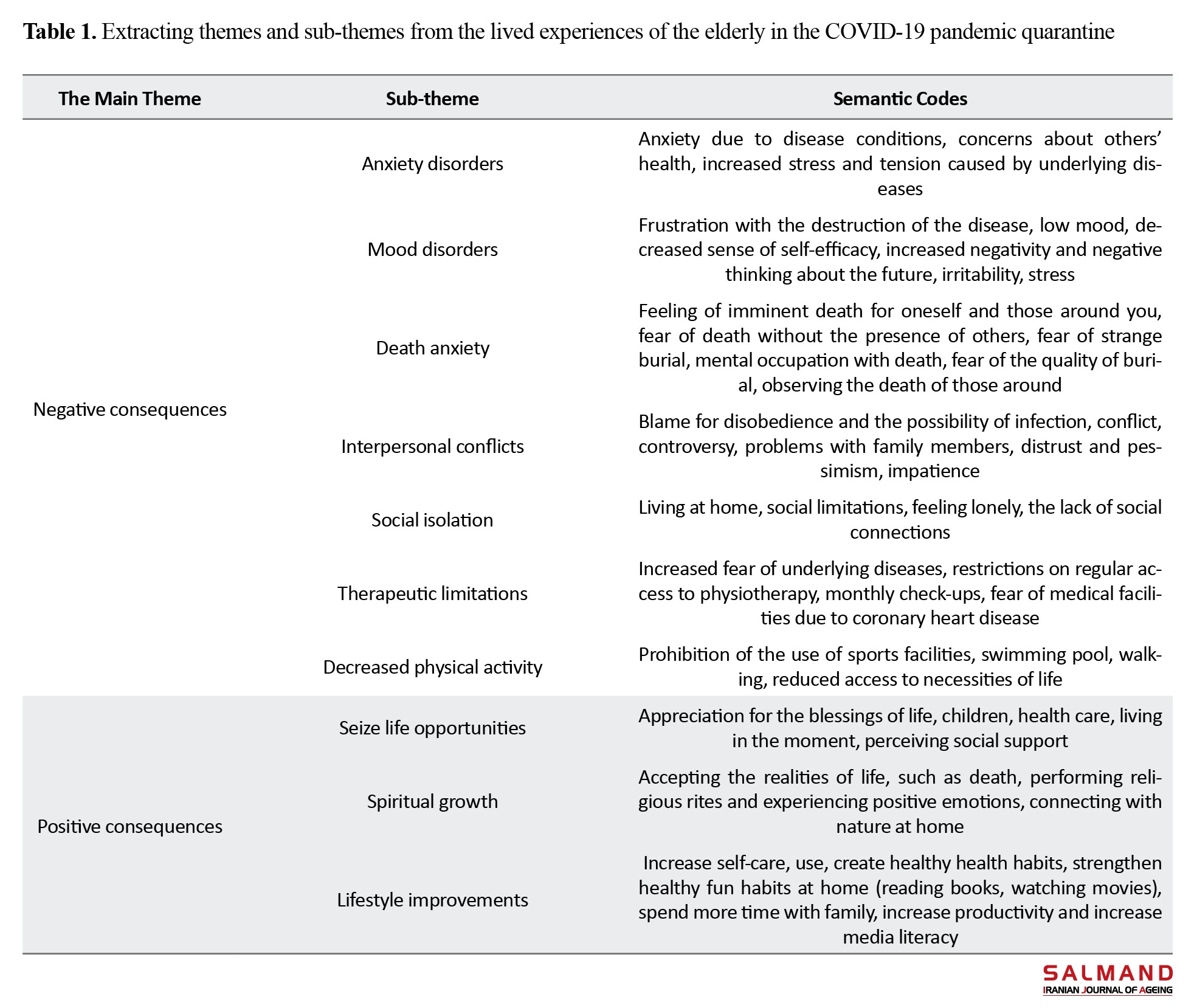

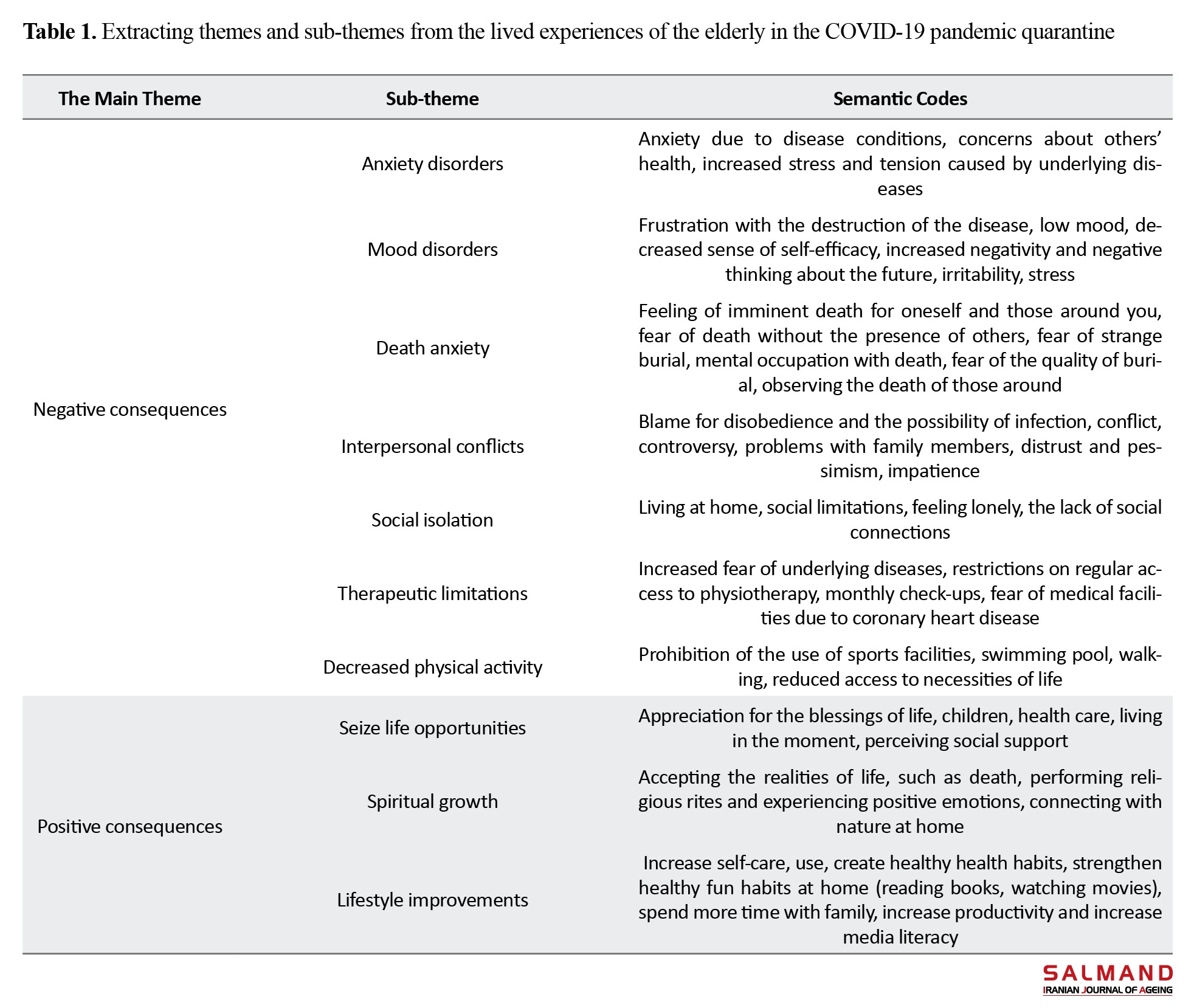

The age of the study participants ranged from 60 to 84 years, their educational level ranged from illiterate to BA degree, and the interviewees presented physical problems. Additionally, 6 participants in the study were females and 4 were males. Table 1 presents the main, sub-themes, and semantic codes.

The first main theme: Negative consequences of quarantine:

Anxiety disorders: This theme includes anxiety due to illness conditions, concerns about the health of others, as well as increased stress and tension caused by underlying illnesses. The elderly, due to certain physical conditions, weakened immune system, ongoing news, and information regarding the vulnerability of the elderly to COVID-19 are at the highest risk of anxiety disorder.

Mood disorders: Disappointment with drugs and vaccines, low mood, a decreased sense of self-efficacy, increased negativity and negative thinking about the future, irritability and stress have reduced their mood.

Death anxiety: The feeling of imminent death for oneself and others, the fear of death without the presence of others, and the fear of strange burial have been common experiences of the elderly.

Interpersonal conflicts: Conflict, quarrels, problems with family members, as well as mistrust and pessimism are some of the things that the elderly have experienced.

Social isolation: This sub-theme is derived from the semantic codes of staying at home, social constraints, loneliness, and the lack of social interaction.

Medical limitations: After the COVID-19 outbreak, the fear of underlying diseases has increased and the affected elderly experienced more stress; due to the special conditions of medical centers and the possibility of developing COVID-19, they encountered limitations to continue the usual treatment process.

Reduced physical activity: The prohibition of the use of sports facilities, swimming pools, walking, are some of the restrictions that have been experienced concerning physical activity in the elderly as a result of quarantine.

The second main theme: the positive consequences of quarantine, i.e., as follows:

Seizing life opportunities: As a result of living in the quarantine for the elderly, positive changes, such as the appreciation of the blessings of life, healthcare, and life at the moment have occurred.

Spiritual growth: Accepting the realities of life, such as death, performing religious rites, connecting with nature in the home space were the semantic codes of this theme.

Lifestyle improvement: This theme was achieved as a result of the semantic codes of increasing self-care, creating healthy habits, strengthening healthy fun habits at home, spending more time with family, as well as increased productivity and media literacy.

The first main theme: Negative consequences of quarantine:

Anxiety disorders: This theme includes anxiety due to illness conditions, concerns about the health of others, as well as increased stress and tension caused by underlying illnesses. The elderly, due to certain physical conditions, weakened immune system, ongoing news, and information regarding the vulnerability of the elderly to COVID-19 are at the highest risk of anxiety disorder.

Mood disorders: Disappointment with drugs and vaccines, low mood, a decreased sense of self-efficacy, increased negativity and negative thinking about the future, irritability and stress have reduced their mood.

Death anxiety: The feeling of imminent death for oneself and others, the fear of death without the presence of others, and the fear of strange burial have been common experiences of the elderly.

Interpersonal conflicts: Conflict, quarrels, problems with family members, as well as mistrust and pessimism are some of the things that the elderly have experienced.

Social isolation: This sub-theme is derived from the semantic codes of staying at home, social constraints, loneliness, and the lack of social interaction.

Medical limitations: After the COVID-19 outbreak, the fear of underlying diseases has increased and the affected elderly experienced more stress; due to the special conditions of medical centers and the possibility of developing COVID-19, they encountered limitations to continue the usual treatment process.

Reduced physical activity: The prohibition of the use of sports facilities, swimming pools, walking, are some of the restrictions that have been experienced concerning physical activity in the elderly as a result of quarantine.

The second main theme: the positive consequences of quarantine, i.e., as follows:

Seizing life opportunities: As a result of living in the quarantine for the elderly, positive changes, such as the appreciation of the blessings of life, healthcare, and life at the moment have occurred.

Spiritual growth: Accepting the realities of life, such as death, performing religious rites, connecting with nature in the home space were the semantic codes of this theme.

Lifestyle improvement: This theme was achieved as a result of the semantic codes of increasing self-care, creating healthy habits, strengthening healthy fun habits at home, spending more time with family, as well as increased productivity and media literacy.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Themes discovered by the phenomenological method obtained new information about the effects of quarantine on the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic; it emphasizes the need to precisely explain the lived experiences of this group, create methods of reconstruction, improve the quality of life, and providing effective solutions based on these themes. Furthermore, according to the positive themes obtained from the research, considering cultural resources, including cultural, Islamic, and spiritual beliefs, can help create a more effective conceptual framework in preventive programs. Without fostering a culture-oriented approach, essential evidence is lost. Eventually, it is suggested that programs to reduce anxiety, including death anxiety, be considered. Given the findings, it seems necessary to increase the understanding of the emotional experiences of the elderly during quarantine.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code:IR.IUMS.REC.1399.226).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study concept and design, data collection, and literature review, data analysis, writing discussion: Shakiba Gholamzad; Writing the introduction and method: Narges saeedi; data collection, and literature review: Shiva Danesh; Data analysis, critical revision of the article: Hadi Ranjbar; writing and final approval: Mahsa Zarei.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Geriatric Clinic of the School of Behavioral Science and Mental Health.

Refrences

- Li L. Challenges and priorities in responding to COVID-19 in inpatient psychiatry. Psychiatric Services. 2020; 71(6):624-6. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ps.202000166] [PMID]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The lancet. 2020; 395(10227):912-20. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8]

- Sun C, Zhai Z. The efficacy of social distance and ventilation effectiveness in preventing COVID-19 transmission. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020; 62:102390. [DOI:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102390] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Henry BF. Social distancing and incarceration: Policy and management strategies to reduce COVID-19 transmission and promote health equity through decarceration. Health Education & Behavior. 2020; 47(4):536-9. [DOI:10.1177/1090198120927318] [PMID]

- Nikpouraghdam M, Jalali Farahani A, Alishiri G, Heydari S, Ebrahimnia M, Samadinia H, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients in IRAN: A single center study. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2020; 127:104378. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104378] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. The Lancet. 2020; 395(10223):470-3. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9]

- Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2020; 9:29. [DOI:10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Armitage R, Nellums LB. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. The Lancet Public Health. 2020; 5(5):e256. [DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X]

- Gerst-Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2015; 105(5):1013-9. [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302427] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lai M-M, Lein SY, Lau SH, Lai ML. Modeling age-friendly environment, active aging, and social connectedness in an emerging Asian economy. Journal of aging research. 2016; 2016:2052380. [DOI:10.1155/2016/2052380] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ferreira LN, Pereira LN, da Fé Brás M, Ilchuk K. Quality of life under the COVID-19 quarantine. Quality of Life Research. 2021; 30(5):1389-1405. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-020-02724-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Asgari M, Choubdari A, Skandari H. [Exploring the life experiences of people with Corona Virus disease in personal, family and social relationships and Strategies to prevent and control the psychological effects (Persian)]. Counseling Culture and Psycotherapy. 2021; 12(45):33-52. [DOI: 10.22054/QCCPC.2020.53244.2453]

- Khodabakhshi-koolaee A. [Living in home quarantine: analyzing psychological experiences of college students during Covid-19 pandemic (Persian)]. Journal of Military Medicine. 2020; 22(2):130-8. [DOI:10.30491/JMM.22.2.130]

- Rahmatinejad P, Yazdi M, Khosravi Z, Shahi Sadrabadi F. [Lived experience of patients with Coronavirus (Covid-19): A phenomenological study (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Psychological Health. 2020; 14(1):71-86. http://rph.khu.ac.ir/article-1-3713-en.html

- Chee SY. COVID-19 pandemic: The lived experiences of older adults in aged care homes. Millennial Asia. 2020; 11(3):299-317. [DOI:10.1177/0976399620958326]

- Brooke J, Clark M. Older people’s early experience of household isolation and social distancing during COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020; 29(21-22):4387-402. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.15485] [PMID]

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008; 62(1):107-15. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x] [PMID]

- Thanakwang K, Soonthorndhada K, Mongkolprasoet J. Perspectives on healthy aging among T hai elderly: A qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2012; 14(4):472-9. [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2012.00718.x] [PMID]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Memaryan N, Rassouli M, Nahardani SZ, Amiri P. Integration of spirituality in medical education in Iran: A qualitative exploration of requirements. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015; 2015:793085. [DOI:10.1155/2015/793085] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Fourth generation evaluation. California: Sage; 1989. https://books.google.com/books/about/Fourth_Generation_Evaluation.html?id=jQpHAAAAMAAJ&source=kp_book_description

- Caleo G, Duncombe J, Jephcott F, Lokuge K, Mills C, Looijen E, et al. The factors affecting household transmission dynamics and community compliance with Ebola control measures: a mixed-methods study in a rural village in Sierra Leone. BMC public health. 2018; 18:248. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-018-5158-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Desclaux A, Badji D, Ndione AG, Sow K. Accepted monitoring or endured quarantine? Ebola contacts’ perceptions in Senegal. Social Science & Medicine. 2017; 178:38-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.009] [PMID]

- Uribe-Rodriguez AF, Valderrama L, DurÁN Vallejo D, Galeano-Monroy C, Gamboa K, Lopez S. Developmental differences in attitudes toward death between young and older adults. Acta Colombiana de Psicología. 2008; 11(1):119-26. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-91552008000100012

- Hacihasanoğlu R, Yildirim A, Karakurt P. Loneliness in elderly individuals, level of dependence in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and influential factors. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2012; 54(1):61-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2011.03.011] [PMID]

- Santini ZI, Jose PE, Cornwell EY, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, et al. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health. 2020; 5(1):e62-70. [DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0]

- Jiang X, Niu Y, Li X, Li L, Cai W, Chen Y, et al. Is a 14-day quarantine period optimal for effectively controlling coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? MedRxiv. 2020. [DOI:10.1101/2020.03.15.20036533]

- Tan M, Karabulutlu E. Social support and hopelessness in Turkish patients with cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2005; 28(3):236. [DOI:10.1097/00002820-200505000-00013] [PMID]

- Liu C, Wang H, Zhou L, Xie H, Yang H, Yu Y, et al. Sources and symptoms of stress among nurses in the first Chinese anti-Ebola medical team during the Sierra Leone aid mission: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2019; 6(2):187-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.03.007] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Geriatric

Received: 2020/11/18 | Accepted: 2021/04/12 | Published: 2021/04/01

Received: 2020/11/18 | Accepted: 2021/04/12 | Published: 2021/04/01

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |