Volume 18, Issue 3 (Autumn 2023)

Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing 2023, 18(3): 396-409 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sadri M, Taheri-Kharameh Z, Koohpaei A. Factors Affecting the Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccines by Older People in Qom, Iran Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing 2023; 18 (3) :396-409

URL: http://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2469-en.html

URL: http://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2469-en.html

1- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Spiritual Health Research Center, Faculty of Health and Religion, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. ,z.taherikharame@gmail.com

3- Department of Occupational Health, Research Center for Environmental Pollutants, School of Health, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran.

2- Spiritual Health Research Center, Faculty of Health and Religion, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. ,

3- Department of Occupational Health, Research Center for Environmental Pollutants, School of Health, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 5165 kb]

(1289 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3543 Views)

Full-Text: (1649 Views)

Introduction

COVID-19 affected most parts of the world [1]. Due to underlying diseases, older people are at higher risk of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths [2]. So far, no fully effective treatment for this disease has been found to the world; therefore, it is important to perform preventive measures [3]. One of these measures is vaccination [4]. The issues related to the acceptance of vaccination have existed for a long time [5]. There is also a lack of distrust in COVID-19 vaccines [6]. It is important for healthcare providers and policymakers to recognize the key factors that explain a person’s intention to be vaccinated [6]. One of the theories that explain health behaviors is the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [7]. The present study aims to identify the factors affecting the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines by the elderly in Qom, Iran.

Methods

This is a correlational study with causal modeling that was conducted in 2021 on 200 elderly members of the Social Security Retirement Center in Qom City, who were selected by simple random sampling. Inclusion criteria were: active member of the retirement center, age >60 years, a reading and writing literacy, and willingness to participate in the study. Failure to complete the questionnaire and not cooperating with the research team were the exclusion criteria. To collect information, a three-part questionnaire was used, which was completed through interviews and by self-reporting method. The first part was related to demographic information. The second part included the TPB constructs, including attitudes, fear, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intention, with 22 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from completely disagree (1 point) to completely agree (5 points). The last part surveys the number of times the COVID-19 vaccine was received. To evaluate the content validity of the questionnaire, 10 experts in health education were asked to provide their opinions. Internal consistency of the tool was evaluated by using Cronbach’s α coefficient which was in the range of 0.68-0.91 for the subscales. For data analysis, partial least squares method was used in SmartPLS software, version 3.

Results

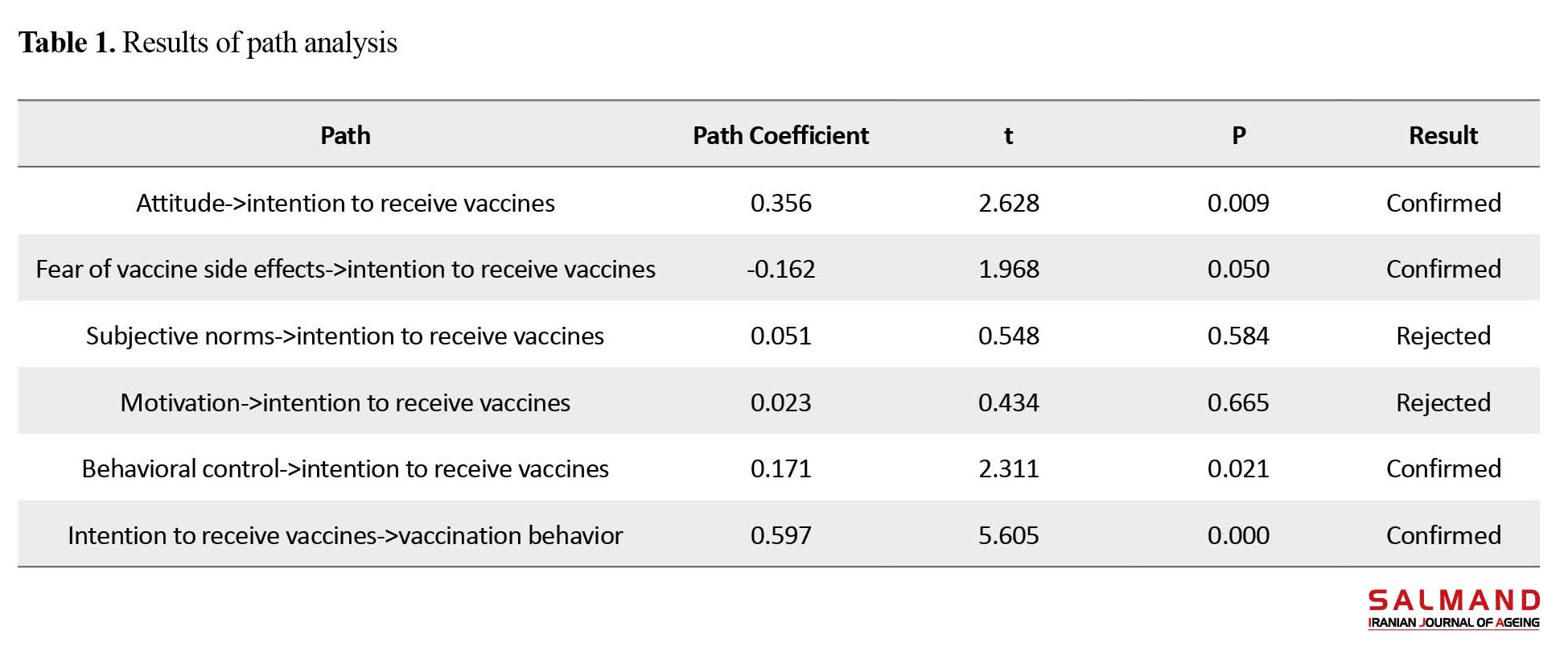

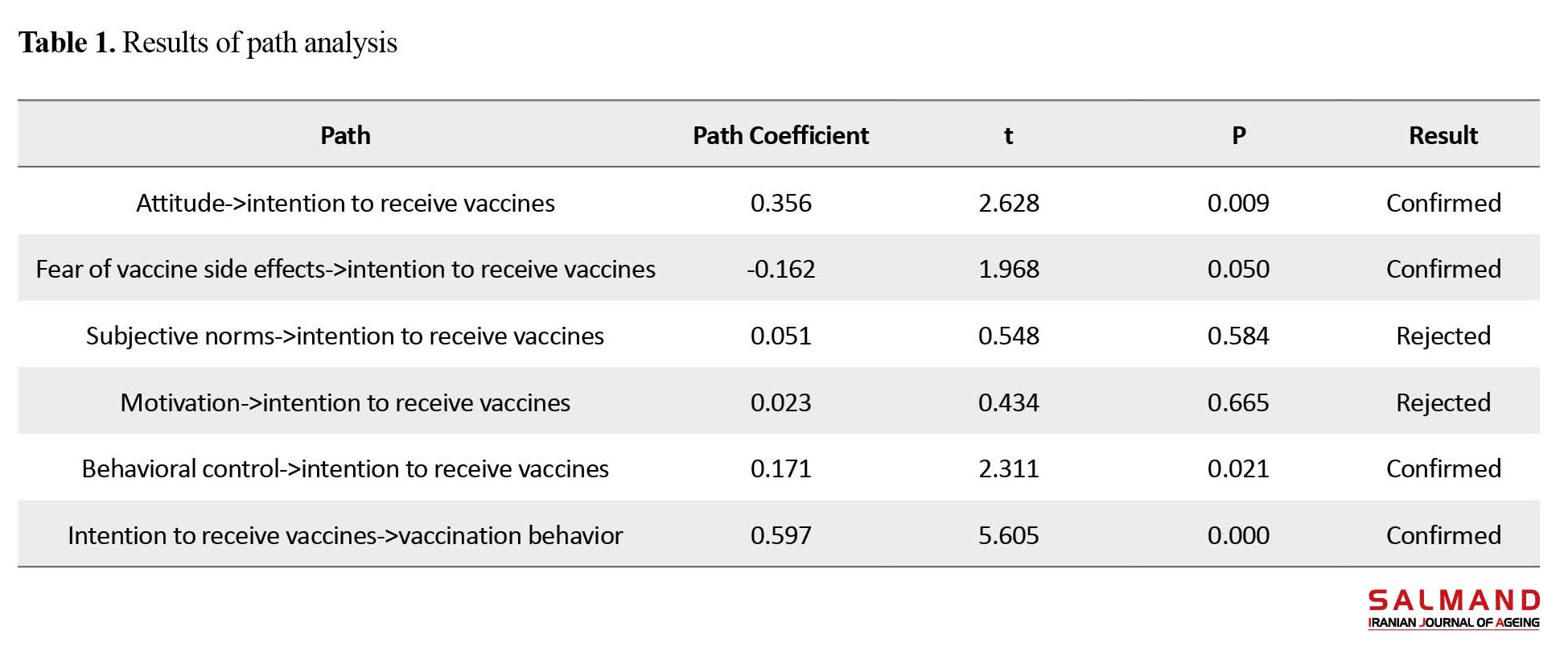

181 out of 200 people completed the questionnaire, and the response rate was 90.5%. The mean age of the participants was 62.8±8.7; 80.1% were male, 27.6% had primary education, and 44.2% had an underlying disease. It was reported that 97.7% had obtained information about COVID-19, mostly from radio and television programs, and 49.7% had received the booster dose of the vaccines. The average percentage of the maximum obtainable score for attitude construct was 77.8%; for the fear of vaccine side effects, 33.4%; for subjective norms, 80.2%; for motivation, 75.6%; for behavioral control, 70.6%; and for intention to get vaccinated, 84.5%. According to the results of the path analysis, which shows the degree of the relationship between the variables, a significant positive relationship between the intention to receive the vaccine and vaccination behavior was observed (β=0.597, and P<0.05). Also fear of vaccine side effects (β=0.162, P<0.05), attitude (β=0.356, P<0.05), and behavioral control (β=0.171, P<0.05) had a significant relationship with the intention to receive the vaccine, while the domains of subjective norms and motivation had no significant relationship with the intention to receive the vaccine (Table 1).

According to the results of model fit indices, the coefficient of determination (R2) for the variables of intention to receive vaccine and vaccination behavior was 0.370 and 0.345, respectively. Therefore, in total, the TPB-based model was able to predict about 34% of the changes in vaccination behavior and 37% of the changes in the intention to receive the vaccine. According to the value of the coefficient of variation for the redundancy index, the quality of the structural model was acceptable. To check the fit of the overall model, the goodness of fit index was used. The obtained value was 0.470, indicating that the overall model had a good fit to the data.

Conclusion

The present study aimed to investigate the intention to receive COVID-19 vaccines among the elderly in Qom using the TPB. According to the results, it seems that the TPB is an efficient model focusing on attitude, perceived behavioral control, and fear in explaining the intention of the elderly for vaccination. It is possible to affect the behavioral intention to vaccination in the elderly by adjusting or controlling the TPB constructs. In this regard, along with the appropriate distribution of vaccines, healthcare providers should make effective efforts to deal with false information about the effectiveness and safety of existing vaccines for COVID-19. Considering that the highest rate of death caused by COVID-19 is among the elderly, it is also necessary to design and implement educational interventions to increase the rate of vaccination in this age group.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The research adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUQ.REC.1400.134).

Funding

This study was supported by Qom University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Methodology: Zahra Taheri-Kharameh and Mohadese Sadri; Investigation and data analysis: Zahra Taheri-Kharameh; Conceptualization, manuscript writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

COVID-19 affected most parts of the world [1]. Due to underlying diseases, older people are at higher risk of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths [2]. So far, no fully effective treatment for this disease has been found to the world; therefore, it is important to perform preventive measures [3]. One of these measures is vaccination [4]. The issues related to the acceptance of vaccination have existed for a long time [5]. There is also a lack of distrust in COVID-19 vaccines [6]. It is important for healthcare providers and policymakers to recognize the key factors that explain a person’s intention to be vaccinated [6]. One of the theories that explain health behaviors is the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [7]. The present study aims to identify the factors affecting the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines by the elderly in Qom, Iran.

Methods

This is a correlational study with causal modeling that was conducted in 2021 on 200 elderly members of the Social Security Retirement Center in Qom City, who were selected by simple random sampling. Inclusion criteria were: active member of the retirement center, age >60 years, a reading and writing literacy, and willingness to participate in the study. Failure to complete the questionnaire and not cooperating with the research team were the exclusion criteria. To collect information, a three-part questionnaire was used, which was completed through interviews and by self-reporting method. The first part was related to demographic information. The second part included the TPB constructs, including attitudes, fear, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intention, with 22 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from completely disagree (1 point) to completely agree (5 points). The last part surveys the number of times the COVID-19 vaccine was received. To evaluate the content validity of the questionnaire, 10 experts in health education were asked to provide their opinions. Internal consistency of the tool was evaluated by using Cronbach’s α coefficient which was in the range of 0.68-0.91 for the subscales. For data analysis, partial least squares method was used in SmartPLS software, version 3.

Results

181 out of 200 people completed the questionnaire, and the response rate was 90.5%. The mean age of the participants was 62.8±8.7; 80.1% were male, 27.6% had primary education, and 44.2% had an underlying disease. It was reported that 97.7% had obtained information about COVID-19, mostly from radio and television programs, and 49.7% had received the booster dose of the vaccines. The average percentage of the maximum obtainable score for attitude construct was 77.8%; for the fear of vaccine side effects, 33.4%; for subjective norms, 80.2%; for motivation, 75.6%; for behavioral control, 70.6%; and for intention to get vaccinated, 84.5%. According to the results of the path analysis, which shows the degree of the relationship between the variables, a significant positive relationship between the intention to receive the vaccine and vaccination behavior was observed (β=0.597, and P<0.05). Also fear of vaccine side effects (β=0.162, P<0.05), attitude (β=0.356, P<0.05), and behavioral control (β=0.171, P<0.05) had a significant relationship with the intention to receive the vaccine, while the domains of subjective norms and motivation had no significant relationship with the intention to receive the vaccine (Table 1).

According to the results of model fit indices, the coefficient of determination (R2) for the variables of intention to receive vaccine and vaccination behavior was 0.370 and 0.345, respectively. Therefore, in total, the TPB-based model was able to predict about 34% of the changes in vaccination behavior and 37% of the changes in the intention to receive the vaccine. According to the value of the coefficient of variation for the redundancy index, the quality of the structural model was acceptable. To check the fit of the overall model, the goodness of fit index was used. The obtained value was 0.470, indicating that the overall model had a good fit to the data.

Conclusion

The present study aimed to investigate the intention to receive COVID-19 vaccines among the elderly in Qom using the TPB. According to the results, it seems that the TPB is an efficient model focusing on attitude, perceived behavioral control, and fear in explaining the intention of the elderly for vaccination. It is possible to affect the behavioral intention to vaccination in the elderly by adjusting or controlling the TPB constructs. In this regard, along with the appropriate distribution of vaccines, healthcare providers should make effective efforts to deal with false information about the effectiveness and safety of existing vaccines for COVID-19. Considering that the highest rate of death caused by COVID-19 is among the elderly, it is also necessary to design and implement educational interventions to increase the rate of vaccination in this age group.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The research adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUQ.REC.1400.134).

Funding

This study was supported by Qom University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Methodology: Zahra Taheri-Kharameh and Mohadese Sadri; Investigation and data analysis: Zahra Taheri-Kharameh; Conceptualization, manuscript writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Korn L, Siegers R, Eitze S, Sprengholz P, Taubert F, Böhm R, et al. Age differences in covid-19 preventive behavior. European Psychologist. 2022; 26(4):359-72. [DOI:10.1027/1016-9040/a000462]

- Sahin AR, Erdogan A, Agaoglu PM, Dineri Y, Cakirci AY, Senel ME, et al. 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: A review of the current literature. EJMO. 2020; 4(1):1-7. [Link]

- Guarner J. Three emerging coronaviruses in two decades: The story of SARS, MERS, and now COVID-19. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2020; 153(4):420-1. [DOI:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa029]

- Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus pandemic 2021 [Internet]. 2021 [Updated 2023 October 08]. Available from: [Link]

- Asgari M, Choobdari A, Sakhaie S. [The analysis of psychological experiences of the elderly in the pandemic of coronavirus disease: A phenomenological study (Persian)]. Aging Psychology. 2021; 7(2):123-7. [Link]

- Chen J, Qi T, Liu L, Ling Y, Qian Z, Li T, et al. Clinical progression of patients with COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. Journal of Infection. 2020; 80(5):e1-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.004] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Pezeshki MZ, Shojaeefar E. [The necessity of urgent low-cost epidemiological studies with short duration about the role of BCG vaccine in preventing and controlling of COVID-19 in Iran (Persian)]. Payesh (Health Monitor). 2020; 19(2):139-44. [DOI:10.29252/payesh.19.2.139]

- Bish A, Michie S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2010; 15(4):797-824. [DOI:10.1348/135910710X485826] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature. 2020; 586(7830):516-27. [DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2798-3] [PMID]

- Patwary MM, Bardhan M, Disha AS, Hasan M, Haque MZ, Sultana R, et al. Determinants of covid-19 vaccine acceptance among the adult population of bangladesh using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. Vaccines. 2021; 9(12):1393. [DOI:10.3390/vaccines9121393] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tumban E. Lead SARS-CoV-2 candidate vaccines: Expectations from phase III trials and recommendations post-vaccine approval. Viruses. 2021; 13(1):54. [DOI:10.3390/v13010054] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Graham BS. Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science. 2020; 368(6494):945-6. [DOI:10.1126/science.abb8923] [PMID]

- Shimabukuro T, Nair N. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. JAMA. 2021; 325(8):780-1. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2021.0600] [PMID] [PMCID]

- WHO. Covid-19 vaccines: Safety surveillance manual. Geneva: WHO; 2020. [Link]

- Hotez P. America and Europe's new normal: The return of vaccine-preventable diseases. Pediatric Research. 2019; 85(7):912–4. [DOI:10.1038/s41390-019-0354-3] [PMID]

- Dubé E, Vivion M, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implications. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2015; 14(1):99-117. [DOI:10.1586/14760584.2015.964212] [PMID]

- Yahaghi R, Ahmadizade S, Fotuhi R, Taherkhani E, Ranjbaran M, Buchali Z, et al. Fear of covid-19 and perceived covid-19 infectability supplement theory of planned behavior to explain Iranians' intention to get covid-19 vaccinated. Vaccines. 2021; 9(7):684. [DOI:10.3390/vaccines9070684] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Trogen B, Oshinsky D, Caplan A. Adverse consequences of rushing a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: Implications for public trust. JAMA. 2020; 323(24):2460-1. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.8917] [PMID]

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021; 9(2):160. [DOI:10.3390/vaccines9020160] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fan CW, Chen IH, Ko NY, Yen CF, Lin CY, Griffiths MD, et al. Extended theory of planned behavior in explaining the intention to COVID-19 vaccination uptake among mainland Chinese university students: An online survey study. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2021; 17(10):3413-20. [DOI:10.1080/21645515.2021.1933687] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self‐efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002; 32(4):665-83. [DOI:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991; 50(2):179-211. [DOI:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T]

- Sommestad T, Karlz H, Hallberg J. A meta-analysis of studies on protection motivation theory and information security behaviour. International Journal of Information Security and Privacy. 2015; 9(1):26-46. [DOI:10.4018/IJISP.2015010102]

- Callaghan T, Moghtaderi A, Lueck JA, Hotez P, Strych U, Dor A, et al. Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Social Science & Medicine (1982). 2021; 272:113638. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113638] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rhodes A, Hoq M, Measey M-A, Danchin M. Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20201; 21(5):e110. [DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30724-6] [PMID]

- Syed Alwi SAR, Rafidah E, Zurraini A, Juslina O, Brohi IB, Lukas S. A survey on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and concern among Malaysians. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):1129. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-11071-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rich A, Brandes K, Mullan B, Hagger MS. Theory of planned behavior and adherence in chronic illness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015; 38(4):673-88. [DOI:10.1007/s10865-015-9644-3] [PMID]

- Hagger MS, Hamilton K. Effects of socio-structural variables in the theory of planned behavior: A mediation model in multiple samples and behaviors. Psychology & Health. 2021; 36(3):307-33. [DOI:10.1080/08870446.2020.1784420] [PMID]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta‐analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001; 40(4):471-99. [DOI:10.1348/014466601164939] [PMID]

- Qiao S, Tam CC, Li X. Risk exposures, risk perceptions, negative attitudes toward general vaccination, and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among college students in South Carolina. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2022; 36(1):175-9. [DOI:10.1101/2020.11.26.20239483] [PMID]

- Gagneux-Brunon A, Detoc M, Bruel S, Tardy B, Rozaire O, Frappe P, et al. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2021; 108:168-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.020] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Detoc M, Bruel S, Frappe P, Tardy B, Botelho-Nevers E, Gagneux-Brunon A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine. 2020; 38(45):7002-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.041] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wang PW, Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Chen IH, Yen CF, Kuo YJ, et al. Motivation to have COVID-19 vaccination explained using an extended protection motivation theory among university students in China: The role of information sources. Vaccines. 2021; 9(4):380. [DOI:10.3390/vaccines9040380] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Shmueli L. Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):804. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-021-10816-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen Y, et al. Behavioral intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese factory workers: Cross-sectional online survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021; 23(3):e24673. [DOI:10.2196/24673] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sturman D, Auton JC, Thacker J. Knowledge of social distancing measures and adherence to restrictions during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 2021; 32(2):344-51. [DOI:10.1002/hpja.443] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cordina M, Lauri MA, Lauri J. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, vaccine hesitancy and intention to take the vaccine. Pharmacy Practice (Granada). 2021; 19(1):2317. [DOI:10.18549/PharmPract.2021.1.2317] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Guidry JP, Laestadius LI, Vraga EK, Miller CA, Perrin PB, Burton CW, et al. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. American Journal of Infection Control. 2021; 49(2):137-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Clinical

Received: 2022/06/22 | Accepted: 2022/11/09 | Published: 2023/10/01

Received: 2022/06/22 | Accepted: 2022/11/09 | Published: 2023/10/01

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |